I have always listened to the radio. The sound covers you, you feel surrounded, accompanied. It was even how I followed soccer games as a student.

So switching to podcasts was quite natural. Quickly, I realized my greediness for the podcasts and my ability to concentrate increased a lot. What was the reason for this? They were talking about me. People were talking like me. Finally, I realized that it was about “us”. The questions, the words, were those of our “girls’ nights” or those of our thoughts, if not secret, then simply kept quiet.

When these shows came out, they showed, deconstructed, proved, told, denounced. Women were speaking out massively, it was new.

At the end of July, I was listening to episode 63 of “Les Couilles sur la table”The journalist received the sociologist Jean-Claude Kaufmann, who was invited to talk about his latest book Pas envie ce soir[“I don’t feel like it tonight”], which talks about consent in couples. The show, which has a great audience, triggered a lot of comments denouncing the sociologist’s remarks. It musts be said that he is not making a big deal of lace when he explains, for example, that women sometimes send signals that are too weak and thus prevent men from understanding that they do not consent to sexual relations. They would therefore be implicated in their marital rape. Victoire Tuaillon, on the verge of choking, tries to counter-argue, but her guest does not disassemble himself by systematically answering that he “does not judge” and only “notes the facts”.

On the other side of the radio, with a certain urge to scream, I wonder: aren’t we living in Mr. Kaufmann’s world? It is for this reason that feminist movements continue their struggles, with a simple demand, dare I say it, a demand to be subjects in their own right and not objects, whose container and contents are commented on, advised, insulted, touched and penetrated at will.

If #MeToo has contributed to free speech, each space has its own rules and habits of silence. In the 2017 movement , everything was denounced in a jumble and some people finally realized the magnitude of the problem, but not everything could be freed and, above all, changed in one time.

They speak, in bulk, about the looks, the humiliations and the ignorance of adults in general. Their sorority jumps to the face

The hope of a new generation?

When I meet Emma*, Alice*, Anaëlle*, Anaïs*, Abby*, Lucie* and Charlotte, they are half excited, half feverish. We met up in front of their school, the Pierre Corneille high school in La Celle Saint-Cloud, where they are all in 11th grade (première).

While waiting for them, I watch a sports class. A kind of nostalgia invades me. Yes, high school is a long way off. However, the memories go back even to middle school. The teacher watching the girls change in the locker room, “his favorites” who seemed to hate his presence, guys in the class who said they “did it” when their girlfriends didn’t even understand what they were talking about.

So to see them there, eager to tell about their struggle and what they think of feminism, is already a victory. It was Emma who organized everything. She also made sandwiches for her friends who couldn’t afford to eat out. We set up on a picnic table in a nearby park.

They speak, in bulk, about the looks, the humiliations and the ignorance of adults in general. Their sorority jumps to the face. For our meeting, they did everything to get together despite very different schedules. They didn’t wait until Monday, September 14th — the day the high school students protested against the establishments imposing a dress code on female students — to be angry, because the discrimination is not new. Are they feminists? “It’s just a question of equality, so yes, we’re all feminists.”

Sentences are flowing, teenage girls obviously need to talk: “We are told that it excites and distracts boys. But it’s not up to us to change!” “But it’s never because of the tank top, it’s because of the guy.”

Violently reprimanded by a male supervisor, Alice tells her shock. She did not give up, however: today she is wearing the object of the crime, the infamous crop top. “I’m afraid of reprisals, but it makes me want to change things because I know that we are full of people thinking what we think.”

In their words, misogyny comes from adults. Speaking of a young girl, one of them says, “she is not a feminist, she looks like a 50-year-old mother.” Another sums up: “We are not the problem, not the students. It’s the adults.”

They are not against the rules and fully understand the need for a framework in the institution. What questions them, aside from the background which they easily call sexism, is the fact that they do not have answers. “When you ask why, you never get an answer. You feel that it’s mechanical, there’s no argument.”

In the middle of our conversation, one of them is called by a boy who just nods his head to tell her that she has to find him. She gets up, her friends mumble: “He’s not a good guy.” I take this opportunity to ask if the problem is only with adults. They look at each other, yes, not everything is rosy in the world of teenagers either. They recognize this and add: “It would be nice if guys were more supportive. I think there’s a majority of guys who support us, but they don’t do enough.” They would also like to have real spaces to talk and sex education classes, which are sorely lacking. “We had one once in middle school to explain to boys what periods are.” One of them, insisting on the abysmal level of ignorance, says, “There’s one who didn’t even know what a vulva and clitoris were,” triggering general hilarity.

A study by the association En avant toutes published by several media on October 6 shows that 16-25 year olds are not spared from violence. Most of the violence is perpetrated by their boyfriends or ex-boyfriends. Nothing new, it is the entourage that is the most dangerous. On the other hand, according to the study, younger people talk about it more quickly around them. A glimmer of hope.

New stage: to the heart of the silences

The first time I was confronted with violence in a couple, I was a teenager watching Thelma and Louise.It took me a long time to realize that Thelma couldn’t go home. In the face of outside violence, she had no choice but to flee. This film exposes the cruel inequality, but also the sorority. It was released in 1991. That year, marital rape was not yet recognized by French law.

Since #MeToo, not a month goes by without a profession revealing the problems of its sector. The cinema, the press, and recently the advertising, music and opera communities with the Instagram page @balancetonagency [@denounceyouragency], accusations against rapper Moha La Squale and soprano Chloé Briot who filed a complaint against a colleague for sexual assault.

The process of women’s stories being voiced and heard continues to move forward. All this makes noise and in the thick silence of the violence, the din is bound to do some damage.

Little by little, we are getting closer to the heart of this silence, the one that suffocates more easily, because we are in confidence, among friends and family. Domestic violence has begun to make the headlines. From psychological and physical violence to feminicide.

In this society of traumatized people, there is of course the possibility, perhaps even the temptation, to totally exclude men from one’s life. Some women have recently indicated that they make this choice from a cultural point of view

What remains? What is this silence that still resists this healthy din? The heart of the heart. Incest. One of the podcasts of this new school year seeks precisely the causes of this silence. It is the documentary Ou peut-être une nuit[“Or maybe one night”], produced by Louie Media.

Returning to #MeToo, Charlotte Pudlowski, the journalist and voice of this documentary tells us: “I remember all these stories that come out, all these blows against silence (…) we talk about colleagues, friends, relatives, but I don’t see anyone writing on Facebook, my father raped me too, my grandfather too, my uncle, my cousin, my big brother.”

Yet the data is there. Dorothée Dussy, anthropologist interviewed in Ou peut-être une nuit: “Between 7 and 10% of the population experiences sexual abuse in the form of rape. The average starting age is 9/10 years old, which means that out of a class of 5th graders (CM2), say, out of a class of 30 students, there are three who experience sexual abuse in their families.”

The anthropologist who describes incest as something that “devastates within” was not surprised by the number of victims, she expected it. “My surprise,” she says, “is how it is possible that there are so many people suffering so much.” And she wonders “how our society lives with” these people who suffer so much.

Help us tell the world to you !

Frictions is launching its club : by supporting Frictions, you’ll be supporting a community of authors and journalists who tell the world through intimate stories!

With or without men?

In this society of traumatized people, there is of course the possibility, perhaps even the temptation, to totally exclude men from one’s life. Some women have recently indicated that they make this choice from a cultural point of view. This is the case, for example, of Alice Coffin, elected ecologist to the Paris Council. In her book Le Génie lesbien[“The Lesbian Genius”], she writes “I no longer read books written by men, I no longer watch their films, I no longer listen to their music. I try at least. (…) Men’s productions are the extension of a system of domination. They are the system. Art is an extension of the male imagination. They have already infested my mind. I preserve myself by avoiding them. Let’s start this way. Later, they can come back.” These words have earned her threats and insults. They have also earned her immense support from feminists, some of whom have posted photos of their exclusively female readings. They also pointed out that Alice Coffin’s words aroused more indignation than the situation of women who still do not live in safety.

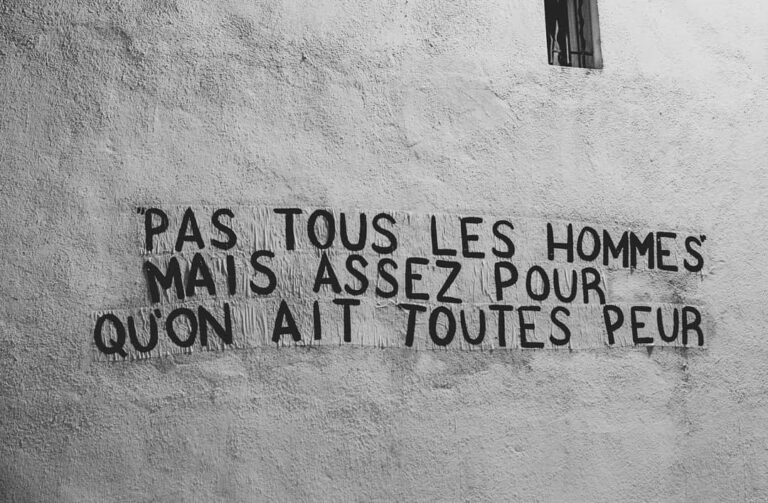

Not only is violence overwhelmingly suffered by women and girls, but the aggressors are even more predominantly men. When you look at the numbers, it makes you dizzy. It’s hard to imagine equality under these conditions and it’s not surprising that the women’s discussions are like a giant talking group.

Failing to prevent, we liberate and try to treat. Let’s dare to hope to prevent tomorrow, with a simple recipe delivered by the wise words of Anaïs, one of the high school girls of Celle Saint-Cloud: “The more we educate the guys, the less trouble we’ll have afterwards, so let’s educate the guys well.”

And one day, as soon as possible, we’ll find the archives of “Les Couilles sur la table” again, and Mr. Kaufmann’s words will have become as dated and unbearable as the sound of chalk squeaking on schoolchildren’s blackboards.

* Names have been changed.