While browsing through my Facebook newsfeed, a colored photograph of a girl with Eurasian features, a bobbed haircut and an identification number worn around her neck appears. My first thought: it’s a tasteless remake of the tragically well-known black-and-white portraits of the detainees incarcerated at the S-21 torture center in Phnom Penh. The prisoners were accused of conspiring against the Khmer Rouge revolution and were systematically photographed upon arrival. A quarter of the population had been eradicated by the time the totalitarian communist regime fell, at which time the pictures were discovered. That same place has become the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, where some of the photos are now exhibited.

My encounters with problematic works of art related to Cambodia have not been rare over my artistic career. There was one musical in particular for which I had been asked to shoot a music video in an S-21 prison cell. It appears as though the Cambodian genocide arouses a twisted fascination in some artists — who then contort it to their wishes. Born in France, a child of Cambodian refugees, I carry the scars of that tragic past, though I did not face it directly. I live in Phnom Penh now, and I have come to a kind of peace with that history. Be that as it may, I am still on guard when I encounter artworks whose subjects are the Khmers Rouges.

Wary, I click on the photo’s link. It brings me to an article published by VICE magazine. The content: 9 colorized photographs of S-21 detainees, as well as an interview with the author of the work, a “self-taught artist” from Ireland. Deep unease settles over me. Not only are the colors chosen for this “restoration” project highly questionable, the faces are luminous, like they were enhanced with skin-lightening or makeup effects. Their skin seems very light — at odds with the generally darker tones of Cambodians. Some clothes are blue or brown, while the Khmers Rouges only permitted black. Clearly, if the goal were to cling to reality, the self-proclaimed artist must have skipped over the necessary research process, unless he deliberately beautified, whitened, and even westernized the deceased. A morbid, if not abhorrent end goal.

A potential case of a Western savior-complex, furthermore capitalizing on others’ sorrows, thus making “trauma porn” his occupation.

My discomfort is only heightened by the colorizer’s comments gathered for the interview. He recounts how the project began at the request of the victims’ families, which he then continued on his own initiative with the support of the museum. When asked about the unexpected presence of smiles on certain detainees’ faces, he rationalizes that they probably occurred due to natural nervousness (which is especially common in women). He also claims that his intent is to “humanize the tragedy” and to make these images more accessible thanks to his colorization. An invitation to inquire about the services on his different websites concludes the article, a badly disguised commercial emphasis which leads me to suspect that, while the artist boasts raising awareness about the situation, the Cambodian tragedy is being exploited for egocentric and economic reasons. A potential case of a Western savior-complex, furthermore capitalizing on others’ sorrows, thus making “trauma porn” his occupation.

The article garners conflicting reactions. Although some express bewilderment or indignation, many are emotional and sing its praises. I share my unease on social media and with Jean-Sien Kin, a Franco-Cambodian friend who also lives in Phnom Penh. What he finds rocks him even deeper because he collaborated with the Genocide Museum as a graphic designer. He contacts the colorizer immediately, and expresses his discomfort and his reservations as to retouching historical documents, questioning him about how he interpreted the colors. When the artist claims that he had acquired all the necessary permissions, it’s as good as “get lost,” and a sarcastic “I will be sure to run all future projects by you for moral and technical discovery” concludes a second memo. His responses betray a disdainful tone and a lack of sensitivity that reinforce my first impression: for him, Cambodians are there to make him look good. They are a stepping stone, they can only congratulate him, comply without resistance, or just be silent.

As Jean-Sien and I begin to research, we uncover revelation after revelation: the director of the Genocide Museum states that he was never made aware of this project. The Facebook page of the aforementioned ‘artist’ features an animated photo of an Auschwitz detainee whose eyes have been made to blink (a service available starting at €99). An older report on VICE, focusing on one of the colorizer’s earlier pieces ends on the same promotional note. These two articles were done by an Australian intern who has no other published journalistic work. I try to get in touch with her, I call out the news company on social media, I send them messages demanding explanations and a right of reply. None of my demands come of anything.

The next day, Jean-Sien goes over the museum’s database with a fine-tooth comb, searching for the original portraits. He sends me a photo of an original with the altered version, and this message: “JB, I can’t believe my eyes.” The expression of the young prisoner in the first black-and-white photo is grim. In the second, colorized one, he is smiling. This Irish artist did not settle for adding colors, he went so far as to modify the victim’s expression! I gasp for air. I start trembling and, despite myself, some tears fall. For me, these modifications are denying and rewriting history, genocide is made out to be a jolly time. My friend continues his search, going over the thousands of archives and uncovering three other portraits that underwent the same facial falsification, much to his horror. Again, he tries to get VICE’s attention, and still they turn a blind eye.

We’re sitting on a ticking time bomb, but what should we do with it? Should we set it off, and risk inflicting the same shock on others? Or should we try to defuse the situation and avoid hostilities? For that, the media company would have to deign to respond. Exposing the originals would be irrefutable proof of deception. The counterfeiter would be caught red handed: image against image. Where words fall short, the side-by-side photos would speak impactful volumes. Upon reflection, Jean-Sien decides to send the fruit of our efforts to the Cambodian director Rithy Panh and to the renowned Belgian photographer John Vink. The latter passes them on to Twitter.

The bomb is dropped. Its impact: instantaneous.

In a few hours, dozens and then hundreds and then thousands of people express their indignation on social media. Each one voices their incredulity, their disgust, their anger. At first, the uprising comes from the Cambodians, whether they live in the country or are from the diaspora, irrespective of the generation, although the youth have the most vitriol. It disproves the widespread belief that they are not interested in history, that they doubt the very existence of the Khmers Rouges. As I read the comments unfurling, my heart contracts, especially at the ones where Cambodians utter their suffering. The condemnation of the project, limited until then, becomes (almost completely) unanimous. A few voices defending the self-proclaimed artist, or contradicting not him, but “the mob” and “the politically correct,” which I am supposedly a part of.

Soon, a Cambodian-American woman living in the United States takes to Twitter, revealing that one of the victims in the photos is her uncle, that the name and story from the article are entirely false, and that her family had never been contacted for this project. An online petition calling for the article to be removed gathers almost 15,000 signatures, while the tweet that kicked the hornet’s nest totals more than a million views. As the dispute expands, VICE Asia only posts a terse message on its Facebook page, claiming that “it ha[d] been brought to [their] attention that the photographs were modified beyond colorization [and that they] are reviewing the article and considering further action to correct the record.” International press gets a hold of the incident which spreads to the four corners of the world. Things take a turn for the official when the Minister of Culture and Fine Arts of Cambodia — which holds authority over the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum — publishes an incisive announcement in which it disavows having given the authorization to use these images, and calls for the removal of the manipulated photos, and saying that they would take legal action if VICE did not comply.

That same day, about 48 hours after the article was first published online, it is removed. No explanation. Nothing. On his part, the revisionist continues to rebuff the Cambodians who convey their distress to him. In the screenshots of their conversations circulating on social media, he now claims that the families had asked for the smiles to be added, because they wanted to hold onto happy memories of their loved ones.

Heated debate ensues. They need to pay! This fundamental disagreement leads to the departure of one person from the group, who asks for their name to be omitted.

The article being deleted is a first victory, but the wrong doers cannot just sweep this discreetly under the rug without apologizing. Jean-Sien and I create a second petition with several people who are particularly active on social media. Ten or so activists, members of militant associations and artists make up the coalition. Most of them are second-generation Cambodians living in North America that I had not known before. A Facebook group chat is created, and each person is asked to write an individual statement. Once all of the contributions are compiled, I skim over the joint announcement written by a third-party as a whole.

While reading it, the claim of financial compensation for the Cambodian community startles me. I cannot understand why money should be involved, and much less to whom it should be paid. In my opinion, asking for an apology should be the focus of the petition. Not everyone shares it. For some, an apology only matters if it’s paired with reparation. Heated debate ensues. They need to pay! This fundamental disagreement leads to the departure of one person from the group, who asks for their name to be omitted.

Finally, a unanimous compromise is established: encourage donating to well-identified associations. The person who had expressed their doubts is back on board, and we are all happy with our collective effort. The next morning, as I look through my messages, I realize that the group chat has been shut down. As I scroll through the messages that had gone on through the night, I realize that there was some disagreement as to the order of names appearing on the petition, who can be the first to distribute it, who gets the credit… it appears that our alliance did not last long. But that incident has drawn to a close. What’s important is that the petition has been launched.

Shortly after, a statement referring to the article is issued on the VICE website: “The story did not meet the editorial standards of VICE and has been removed. We regret the error and will investigate how this failure of the editorial process occurred.” It’s like a slap in the face. Their only error was publishing an article that did not meet their editorial standards! Not one word regarding the victims, their families, all the people who voiced their pain.

Far from satisfying us, these “non-excuses” give the movement new purpose, and this momentum spurs the creation of a group on Telegram, made up of several people who contributed to the previous petition, as well as others. Several ideas of actions to be taken emerge, but they are unrelated to the case that first united us: attacking a metal band that chose to call themselves ‘Tuol Sleng’, and who are promoting their CDs and merch with a painting by Vann Nath, the painter who survived the S-21 prison; returning spoliated works exhibited in foreign museums to Cambodia; halting the construction of an attraction park near the temples of Angkor…

And then — surprise — VICE publishes a statement in English and in Khmer, presenting its sincere apology to Cambodian communities and families.

These topics are very dissimilar to me. They should not be accorded the same degree of consideration, and don’t all have an identical magnitude. The contemptful and fraudulent manipulation of historical documents which sullies the memory of genocide victims in the accused article was all backed by a well-known international media company, and not a single Cambodian was consulted. Our history is being rewritten without us, at our own expense. As for the other cases, my shock or distaste carries no weight. I have a hard time imagining myself joining other movements that I don’t identify with, and which already seem futile. I have neither the motivation, nor the strength. The ongoing incident is eating away at me: I can’t sleep, I get angry at the slightest inconvenience, I make my friends and family miserable, and I neglect deadlines for work… I need to focus on myself. I’ve done my part.

Several days go by, and I start to recover from this upheaval. And then — surprise — VICE publishes a statement in English and in Khmer, presenting its sincere apology to Cambodian communities and families. It was about time. The head of the petition informs me that a representative from VICE had sent her an email, and asks me if I have any particular complaints to address. I submit what I have requested from the beginning: a right of reply, and that Cambodians have a voice in this chapter. I suggest one or two series of articles that could stem from this incident, as well as some themes, and I reiterate my wish to collaborate with the journalists in the creation of the articles.

Several weeks go by before the petition’s leader contacts me again. She tells me about the telephone interview she had with the Editor in Chief of VICE Asia. They gave a verbal apology, and then laid out the internal action taken: the senior editor in charge at the time of the incident was laid off, people with diverse backgrounds were recruited in order to reinforce the teams, and a training course to promote cultural awareness and inclusivity was created. The people native to a country would be consulted when an article concerned a nation in particular and finally, a series of articles about Cambodia would be published.

All the pledges taken show a real commitment to making amends, and I am overjoyed, but despite everything, my feelings are tinged with bitterness. If these new articles are ever published, it’s unlikely that I would have a hand in them. The proof: VICE has never taken the time to contact me, or to respond to any of my messages. The same goes for Jean-Sien. If we wanted to be on their radar, we would have had to put ourselves first systematically, proclaim ourselves the representatives of the entire community, and exploit the exclusives that we held for our own benefit. But there are many stories yet to be told. I will not wait my turn to speak, and I will not hesitate to speak out every time I deem it necessary.

Help us tell the world to you !

Frictions is launching its club : by supporting Frictions, you’ll be supporting a community of authors and journalists who tell the world through intimate stories!

As for the instigator of the outcry, he has vanished into thin air without so much as a meager apology or a simple expression of remorse. His attitude raises questions. Is there a single element of truth to his words? What were his intentions? To be talked about? To do wrong? I have even wondered if this was a stunt designed to earn him his 15 minutes of fame, though you would have to be pretty disturbed to plan a conspiracy like that. He might not have even gone that far, and simply enjoyed being at the center of all that attention. There’s no point in giving him even more publicity, be it negative. His name is not worth being mentioned. He should be forgotten.

There are better things to remember. Other than the actions taken by VICE from within, the incident of the fake smiles of S-21 had a few consequences worth celebrating. For instance, in order to better regulate the profession’s practices, a collective of colorizers developed an international code of conduct; the metal group mentioned above apologized, changed their name, and stopped using Vann Nath’s paintings. But what will be burned into my memory forever is the incredible cross-continental wave of mobilized Cambodians, carefully safeguarding the memory of those lost. Just for a moment, we managed to pull together. Though it was never up for debate, this misadventure has shown that we are just humble human beings. Through thick and thin, through solidarity and disagreement, through dignity and vanity, through conviction and hesitancy. Neither us nor our stories need to be “humanized” by anyone. And as for those who try to erase our history, to make us disappear in the figurative and literal sense, beware. We will not allow ourselves to be erased.

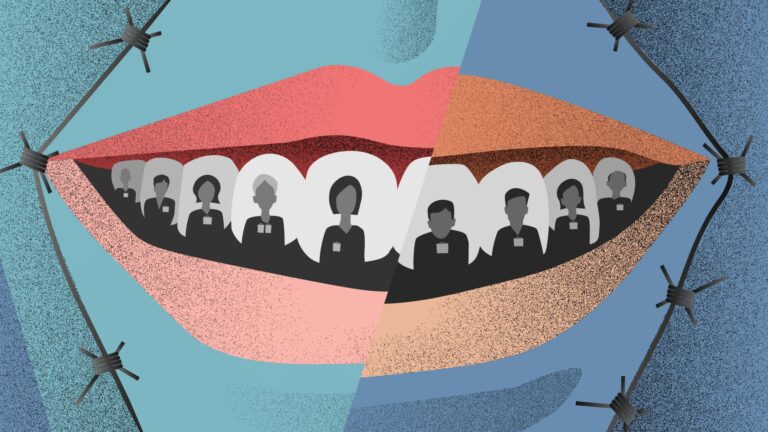

© illustration : J.-S. Kin