“I’m going in tomorrow”

“No, you’re not.”

“Yes I am, and I don’t want to hear another word about it. I’ll leave this conversation and go upstairs right now.”

I was shocked. It was mid-March, and my boyfriend and I were video chatting with his parents. His father, a managing director at a small pensions firm in Surrey, was telling us that despite the obvious risks, he was going into the office tomorrow and he wouldn’t listen to anyone tell him why he shouldn’t.

While we weren’t yet officially in lockdown, many other European countries were. Most UK employers who could had already asked their employees to work from home—including my (small) startup and my boyfriend’s (big) bank. If companies as diverse as ours could make this work, why couldn’t he?

But his determination, his anger, made it clear that “making it work” wasn’t his aim. He wanted to be in the office, and no rational argument could touch that desire. In the midst of a pandemic, a man who shared a household with a wife and daughter deemed vulnerable due to underlying health conditions wasn’t going to stay at home and protect both them and himself.

Something else was at play.

“Industrious work and long hours,” Markovits says, “constitute the eliteness of the working rich” busyness has in itself become ‘the badge of honour

*

Most of us, I suspect, don’t ask ourselves why we work. It’s simply a given of our existence. I got my first “real” job at age 25, still buzzing from the intellectual high of graduate school. I did it because I realised that if I wanted to be able to afford to live in London and hang out with all the cool, smart people I had met at said graduate school, I needed a job. And that was that.

Twelve years later, I still set my alarm every weekday morning. There have been many, many points in those 12 years when I’ve questioned what kind of work I should do. But my assumption that “work” is just something that has to be done has persisted.

For me, the chemical reaction that underpins that assumption looks something like:

Hard work -> Money -> Nice place to live, nice food to eat, holidays to go on -> Happiness

(Or at least all the material pre-requisites for happiness taken care of, with enough money left over to pay a therapist to help me figure out the rest)

I assumed everyone else’s equations looked more or less the same. But there I was, video chatting with a 69-year-old man who was still going into the office even when doing so looked like a clear net negative to his happiness and health.

The work-happiness equation has been breaking down in various ways for a long time, long before Covid-19. The Whitehall Studies, which have been conducted on British civil servants since 1985, have shown correlations between long hours in the office and a host of decidedly unhappy phenomena, including impaired sleep, depressive symptoms, and heart disease.

Daniel Markovitz, in his 2019 book The Meritocracy Trap proposes that these types of findings are indications of something larger, and darker: that the work-happiness equation has broken down for all of us, in almost every sense, because the meritocratic ideal we’ve set up for ourselves is inherently flawed.

Markovits argues that it is meritocracy itself—that cherished liberal ideal—that is to blame for our unhappiness. Meritocracy, most notably in the US, has produced an elite professional class that enjoys an ever-increasing share of society’s wealth. But unlike the elites of old, who revelled in their leisure time because it was a sign of their status, today’s elites revel in their long hours in the office for precisely the same reason, even as those long hours diminish their well-being.

Why do they do this? American elites today have found themselves in a society whose middle class has been hollowed out. They know they can only sustain their advantages (which come, by and large, from having elite parents) by ruthlessly competing—first to attend the best primary schools, then the best universities and graduate schools, then to secure the most prestigious roles in law, medicine, and business.

Today’s elites are generally unhappy, Markovits argues, because they must constantly exploit their human capital (built up through years of elite schooling) in order to win. Yesterday’s aristocrats watched their land and their investments increase in value while they painted or played croquet. Today’s aristocrats derive their wealth from their own labour, and thus they trap themselves in a cycle of unending work.

“Industrious work and long hours,” Markovits says, “constitute the eliteness of the working rich; busyness has in itself become ‘the badge of honour.’

*

If eliteness today were a Manhattan speakeasy with a non-descript door next to a pizza counter for an entrance, the pass phrase would undoubtedly be “I’m so busy.”

For those of us (and I include myself in this group) who have been snapped up into Markovits’ meritocracy trap, busyness is what must be projected in every social interaction. It a signifier of tribal affiliation, a mark of allegiance.

“I don’t know about you, but I think the insanity has reached another level this week,” says a colleague in our weekly catch-up.

“I know how busy you are. I’ve seen your calendar,” says another. It feels like a show of deference, a lord bowing before his queen.

On social media, the story is the same.

“Where do you find the time??” comments my friend’s sister-in-law, reacting to an Instagram photo of homemade scones sitting on a tiered cake stand. The subconscious implication: that she must not be working hard enough. (This friend, as it happens, is a doctor who’s raising three kids. I suspect she is, in fact, working hard enough.)

For my tribe—the highly educated, professional, mostly white American and European thirty-somethings of the early 21st century—busyness has become goodness. A crowded calendar is tangible evidence that we are both wanted and needed by our peers, and that we are spending enough of our time working to fill those orders that our peers have placed with us. We’re paying our dues. We’re not being selfish .

Busyness is how we show each other that we belong.

*

The irony, of course, is that this good, unselfish busyness that we’ve spun up into a moral principle is just a new view on what is fundamentally a selfish act: make money, buy things, pass the leftovers to one’s children, rinse, repeat.

Busyness is also a way to paper over other sins. I was recently invited by a startup CEO to have lunch in Kensington, a tony corner of west London. He was looking for a head of marketing, I was half-heartedly looking for a new job, and we had a perfectly pleasant chat over halloumi and salmon. Like every CEO I’ve met, he was a poster child for the busyness principle: early mornings, late nights, weekends on, and a partner who “wishes she saw more of me, let’s just put it that way.”

We must stand in front of our mirrors and reckon with the fact that we sit in front of small screens for 12 hours a day and call it a life

I didn’t get that job. But on the way back from lunch, I started Googling this man and his company, and found out that he had been involved in a terrible tragedy: he had drink driven one night while at university, and had gotten into a crash that killed his close friend. He served six years in jail, then finished his degree and started building his company. Frantically working, creating and nurturing a company was for him, I suspect, a way of erasing the past.

His is an extreme case, at first glance. But then I think of my friends. The one who was bullied as a kid and now takes unbridled delight at having more money and a better career than his schoolyard enemies. The one who’s afraid he’ll never be as successful as his famous father, who proves his worthiness through sheer devotion to his job. The one who hasn’t had a full-time job in more than two years, who discharges her obligation to busyness by running and attending fitness classes to the point of exhaustion.

We are all expiating some kind of guilt. We are all working ourselves clean.

*

And then, there’s me.

When the pandemic hit, my New-York-based boyfriend flew to London to ride out the storm in my studio apartment. Our long-distance relationship was suddenly transformed into a non-stop assault of togetherness.

For him, the most surprising thing about my unveiled lifestyle wasn’t how hot I like my showers (scalding) or how neatly I like my bed made (not a crease in sight).

It was how much I worked.

And I, for my part, was surprised that he was surprised. Nothing about the way I work felt unusual to me. Back when I commuted to office, I arrived between 9 and 9.30am, left between 7 and 8pm, snuck in more emails and Slack conversations from my phone before bedtime at 10, and set aside Sunday afternoons and evenings to do the larger, focused pieces of work that I couldn’t get done during the week.

Not only did this feel normal and natural. Often, it didn’t feel like enough. For every Sunday I worked, a peer (imagined or real) was working Saturdays too. Fear stalked these hours—fear that my output wouldn’t be good enough, that my colleagues would be unhappy with me, that I would lose my job and have my tribal membership revoked. That I would be alone.

Irvin Yalom, one of my favourite writers, proposes that human life has four “ultimate concerns”: death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness. Fear of these four things underlies most of what humans think and do. Religion ticks all the boxes: fear of freedom (just ask Dostoyevsky), fear of death (just ask Chaucer), fear of isolation (just ask Orthodox Jews, who require that ten adult men be present in order for God to be worshipped), and fear of meaninglessness (just ask the members of the Westboro Baptist Church, whose devotion to rules-based Christianity makes Mussolini look soft).

It seems clear to me is that work is doing for my tribe what piety did for our grandparents and their grandparents. It’s a weapon we use to beat back our fears. Not a sword, because no amount of jousting diminishes the little beasts’ power. It almost always amplifies it.

Work, rather, is a shield that we use to protect ourselves from fear. And in a time of rampant fear, like the one we’re living through today, it’s no wonder that so many of us are polishing up our shields and curling up underneath them.

Help us tell the world to you !

Frictions is launching its club : by supporting Frictions, you’ll be supporting a community of authors and journalists who tell the world through intimate stories!

*

Covid-19 has laid bare a lot of truths that none of us has had to confront before. Among them, I’d propose, is this: busyness-as-piety idea isn’t just for the meritocratic elites. It’s been spreading, slowly but surely, to all corners of society.

Work has been our shield against darkness. Now economic collapse—with its bankruptcies, job losses, and furloughs—has taken the shields from so many of us. And those who are still employed are working in a new way: our button-down shirts have been replaced by yoga pants, our business trips by walks to the dining table. In a very tangible way, the glamourous façade of many professional jobs has been destroyed. We must stand in front of our mirrors and reckon with the fact that we sit in front of small screens for 12 hours a day and call it a life.

I hope our reckoning is a lasting one. If there were ever a time to collectively decide to reject this race to the bottom, it is now.

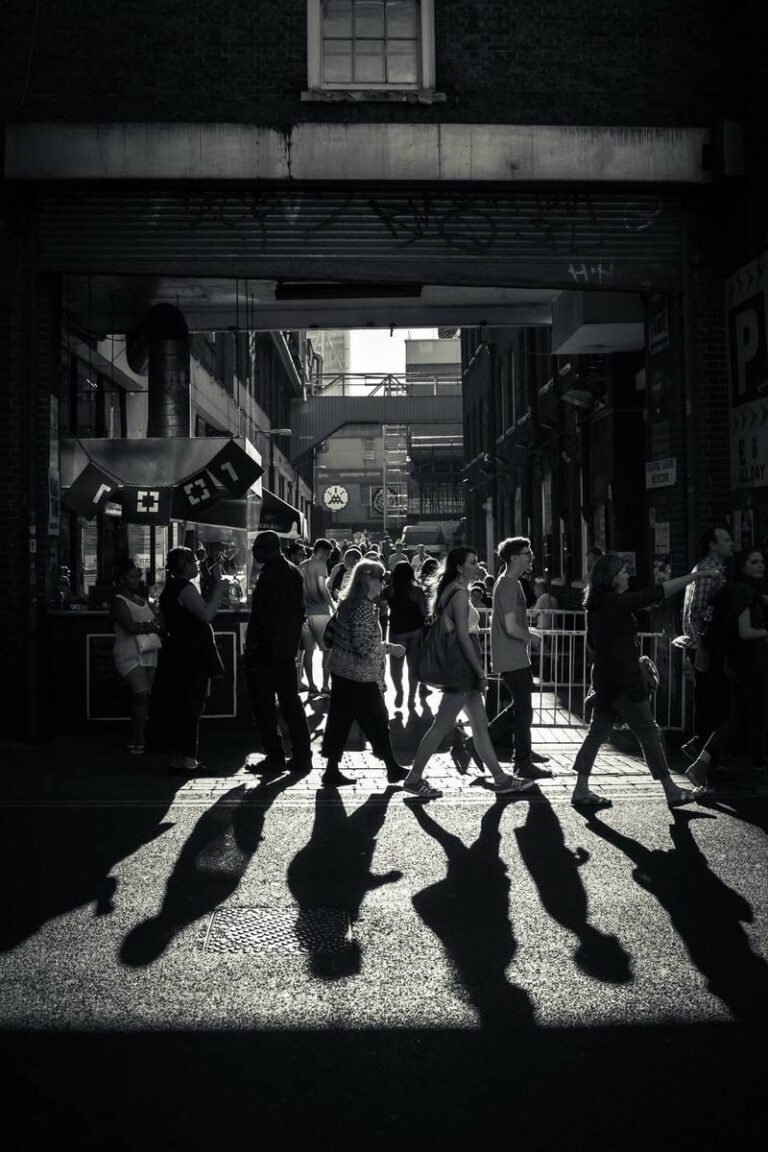

In May, as I write this, my boyfriend’s father is still going into the office every day. We have now officially been in lockdown for over six weeks. Yet there is still post to be opened. And so, each morning, he rises before 6, eats his breakfast, picks up his shield from the bottom of the stairs and carries it out into the gleaming sun.