29/03/2024

Reims.

February 2021.

It is the cultural season “Africa 2020”.

But 2020 is already far away, and so is Africa.

A pandemic has since run riot, disrupting programs drawn up long before.

Nova Villa, an association that works with young audiences in Reims, invited me to co-construct part of the program for this cultural season with them. Several artists, researchers, activists, and influencers living in different countries of the African continent were to be present to embody certain perspectives.

Thanks to Covid, they will not be here.

After some hesitation with Nova Villa, we still decided to sow some of the project’s seeds, while waiting for better conditions to water them.

Aware that my small shoulders as an Afro-descendant raised in France will not allow me to brush against even a thousandth of the reality of the African continent, I opt for a slightly offbeat option. Rather than talking about the continent without those who live in its 54 countries, I propose to work on the representations that we, who live in France, have of it.

The proposal is rooted in an essential dimension of my work as an author: questioning our imaginations, naming the submerged strata, flushing out the social and historical constructs that we are imbued with through our intimate stories.

I therefore invite the students of several middle school and high school classes in the city to tell and intertwine their representations of the African continent.

To do this, we will use the technique of Photolanguage. It’s a tool that is simple and fun. A few dozen images are placed on a table, and everyone chooses one that resonates spontaneously for them. Each then talks about it, responding to three questions: What do I see in this image? Why does it echo when I think of Africa? What are the experiences that have built my representation of this continent (readings, films, courses, personal anecdotes, family stories, travel…)?

Several of the city’s establishments agree to take part in the experiment.

Thus I arrive in Reims with my suitcase on Monday evening, February the 8th.

The next morning, a first class awaits us: 8th Grade.

The corridors of the establishment, the stairs, the noises that resonate here and there remind me of my school years of which I keep rather hazy memories.

We gather around the table, students, teachers, and the Nova Villa team.

We gather around the table, students, teachers, and the Nova Villa team.

I guide the group by explaining the rules of the game.

When I observe what unfolds around the images that I place more and more hesitantly over the three days, I am rather worried for these young French people of African descent who inherit a truncated, mutilated narrative from their ancestors’ continent of origin

It’s never easy for the first to get started.

At last, a young boy in the class, black, decides to start. He chooses, in a corner of the table, the image of a guitar catching fire. He takes the photo, shows it to us and, from there, begins to tell us about it. He starts talking about Africa as a plundered continent: the theft of the continent’s economic and mineral wealth by the West, the degradation that this entails on the continent, its environments, its inhabitants…

I did not see that coming. I tell myself that we’re off to an intense start.

I am quite amazed at the geopolitical insight of such a young teenager.

My astonishment will unfortunately not last very long.

A distorted knowledge

In the days that followed, I met with seven other classes.

One day after another, in the unfolding words, a continuous image of Africa reduced to poverty again and again, to war, and to migrants fleeing on boats. Class after class, the same images over and over.

From time to time, some more exotic scenes appear: the colorful market, the peaks of the desert, the hut in the middle of a small village, the animals of the jungle.

Kirikou has left its mark.

Mainstream media too.

As well as educational and cultural projects evoking Africa only from the angle of migrants leaving by boat.

Not to mention Eurocentric history lessons. Africa is systematically thought of from the angle of lack or delay, and drawn as a territory without civilization or history before European colonization.

In words that are shared, Africa is depicted as a single bloc. The situations addressed (war, famine, sick children, etc.) have no geographical or time limits.

They devour the whole continent.

Questions to invite more context to the stories evoked do not yield much either. Impossible. The African continent is a homogeneous mass, from Cape Town to Rabat via Lagos, Luanda, and Tripoli.

And time stands still there.

At one point, one of the teachers speaks of “eternal Africa”. The expression rings painfully in my ear, like the words of this former French president who declared: “the African man has not entered into history.”

As the week progresses, my dismay grows. The repetition becomes slightly oppressive.

My attempts to diversify and differentiate points of view appear futile. I am painfully aware of how cruelly we are missing the other half of the mechanism, canceled due to the pandemic, namely the presence and stories of multiple speakers living on the continent.

In the middle of the week, one of the classes is a breath of fresh air.

The words of the middle school pupils reveal some contrast: the possibility of an urban Africa; the existence of a social stratification integrating working-, middle- and well-off classes; innovations of the continent’s youth; stories spanning the decades. Petit Pays, the novel by Gaël Faye, read a few months earlier by the students with their French teacher, paved the way for other possible representations.

It is in this very instant that I realize the full power of unique stories. Also of the scope of the school program. And the role of teachers in choosing the content they offer to their classes.

But the rest of the time, I identify with Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina’s ironic article, “How to Write About Africa”, where he reminds the reader that to write about the continent, “An AK-47, a emaciated torso, bare breasts: this is what should be highlighted.”

I also think back to the TED conference where the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie evokes “danger of the single narrative”, one which constantly condemns Africa to being a continent “full of beautiful landscapes, beautiful animals and incomprehensible people, enlisted in senseless wars, dying of poverty and AIDS, unable to speak for themselves, and waiting to be saved, by a kind white stranger.” In the West, throughout our lives, we are fed different versions of this story. The few Nobel and Goncourt prizes, awarded from time to time to a personality from the continent, are hardly enough to reverse the trend.

Of course, I did have these caricatural and unequivocal representations in mind, systematically shared in the West on the African continent. But I am flabbergasted by the extent to which, over the three days, this miserable vision of Africa fills the imagination, leaving no room for anything else. The February temperature, hovering around zero degrees, is not responsible for the chill I feel inside. This repeated performance, again, again and again, for three days, is gradually crushing me.

A part of me curls up, piece by piece, over the course of the hours

and classes encountered.

Among the students, some young people whose families are from the African continent hardly dare to whisper the name of their parents’ country of origin

However, my path takes me to establishments with varied sociological profiles. From affluent neighborhoods, I move on to working-class neighborhoods and their more mixed classes.

Among the students, some young people whose families are from the African continent hardly dare to whisper the name of their parents’ country of origin, this being a request made by some teachers, apparently mystified by these teenagers’ embarrassment even to mention the mere name of the country. It is truly difficult to admit geographical origins when imaginations are so overrun by calamities and horrors. Several times, I see eyes that avoid contact, a few faces that turn only to be seen in profile. Their bodies themselves are like archives of some dirty collective history. They reveal it in modest silence. It’s quite uncomfortable to find yourself with the accumulation of these visions right under your nose.

The violence of the situation only really sinks in several days later, in the aftermath. The apparent calm of our bodies gathered around these tables covered with images contrasts markedly with the violence of what is symbolically unfolding there. I’m petrified. I feel like I have inadvertently set a trap that is closing in on me, and on these young people.

To find something of the incandescence carried by the image of the fiery guitar, chosen by the first teenager, would have at least made it possible to thaw the atmosphere.

Between two days of work, I cross frozen streets of Reims, capital of Champagne.

The hotel room that I return to offers me some respite from these encounters.

Respite and introspection. Questions about collective histories. About my own, too.

I arrived in France at the age of 5, after leaving a country in West Africa that I never name. What I mean by that is that my geographical roots float, in a native country that I know little about. It is also a reminder that my territory of reference, the one from which I speak, think, and act, is France. I’ve hardly known anything else. I belong to what some sociologists have come to call “Generation 1.5”, for lack of a word to describe these experiences of displacement which are only half so.

My memories begin in France. Or rather the day when, in my country of origin, my sister told me that we were going to live in France. If our story starts at the point when we can reminisce, and recall to each other, then I can say that I was born in France. It was August 24, 1988. A few days before school started.

However, I am often asked to participate in events across Africa. While I may repeat that this continent is one I know very little about, it’s often from this very place that I am invited to reflect on my place.

It may be only a family heirloom, distant in both space and time, but strangers who ask me in the street where I come from flatly refuse my answer that I come from Seine-et-Marne.

French maybe, but definitely black: I must first give an account of my African ancestry, situate myself with reference to that place.

So, I try to invent from the debris and nuggets of all that. I try to make it a working material. And, when possible, to involve other people, especially from the younger generation.

This week in Reims was to be a prime opportunity for that. But when I observe what unfolds around the images that I place more and more hesitantly over the three days on the classroom tables, I am rather worried for these young French people of African descent who inherit a truncated, mutilated narrative from their ancestors’ continent of origin. They, like me, are – willingly or by force – custodians of these representations, considered as extensions of the same.

How to grow by positioning oneself as heir to such a story?

We grew up in France but are regularly referred to our parents’ countries of origin, of which we often know nothing or very little. We therefore have these massively disseminated narratives about the African continent as our quasi-unique shared vision, and in counterpoint, a lack of representations of our contemporary realities in France which would allow us to see ourselves in all our complexity. It’s hard not to think of yourself only as an heir of these unfortunate images, and to be very uncomfortable with that. We too are carriers of a derogatory gaze that we cast on our group of origin, and therefore by extension, on ourselves.

It’s not surprising that when we talk about Africa with the Afro-descendant pupils in these classrooms in Reims, we sometimes seem to touch on a kind of taboo. This kind of “lip service to the diaspora”, I also experienced it as a child, at school, when Africa was mentioned and I bowed my head.

How to grow by positioning oneself as heir to such a story?

That week of February 2021 was almost a year ago, but I’m only reporting on it now. I hesitated for a while, procrastinated for a long time, before testifying to it. What more can be said about these questions that has not already been said, thought about, or sometimes shouted? And how to say it so that beyond the facts, it becomes the breeding ground for intimate and collective transformations?

Each time I take the keyboard to write about it, these questions come back and threaten to stop my pen. And then comes the moment, often late at night, when I remember that singular stories, in their accumulation and their multiple perspectives, make it possible to anchor experiences that are constantly threatened with invisibility. May they participate in giving our voices a breadth and consistency to enable them to be heard.

So I tell these stories here, to continue to densify the concentric circles that I have been drawing for a few years around black experiences in France. Also because sometimes a spark may fall and revive some embers.

Help us tell the world to you !

Frictions is launching its club : by supporting Frictions, you’ll be supporting a community of authors and journalists who tell the world through intimate stories!

During that week in Reims, the spark leapt on the final day.

On the Friday, I brought a slightly different set-up to the students. We leave aside the question of Africa, to look specifically at being of African descent with students in two high school classes. At my side, N’Fanteh Minteh, TV journalist. She is French, born to Gambian parents who arrived in France before her birth.

We each tell our experiences as “blacks of France”, both French and Afro-descendant, heirs to these stories. The students who hear our experience in these two classes, numerous, then make themselves heard, coming out of their shy silence.

From their fervor and their involvement in the discussions, I tell myself that they rarely have the opportunity to speak and be heard on these issues within the school. Together, we search for the shared words, to reclaim this narrative. Afropeans, blacks from France, Generation 2, simply French…? I have the impression that there is something quite liberating in putting this shared experience into words, for them, as for N’Fanteh and me.

Something restorative even.

Coming out of there, I see the extent of the work to be done to move forward on our experiences.

It seems colossal to me. I have the feeling that neither a whole lifetime nor a generation would be enough. I tell myself that I will have to concentrate my energy, set a perimeter of action within which I may feasibly mobilize the ammunition at my disposal.

Multiply these spaces wherein young French Afro-descendants can share around these questions. Address how our imaginations have been infused, intoxicated, by this unique story. Complicate them.

Also tell of our emptiness, our abysses, our doubts. Our resources too. Our questions, our discouragements, our joys too.

Shine a light on our zones of desperation as well as where hopes remain.

To heal, to strengthen.

Love yourself better too.

Explore

Naturalization: a step on the winding road to dual identity

How can a tiny piece of paper — an identity card — have such an impact on a life, an identity?

Palestinians in Lebanon : being and wanting to truly exist

In the spring of 2021, an 11-day war between Israel and Palestine erupted, initiating a period of anxiety and anger for the approximately 260,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. However, this conflict is also a source of hope and pride.

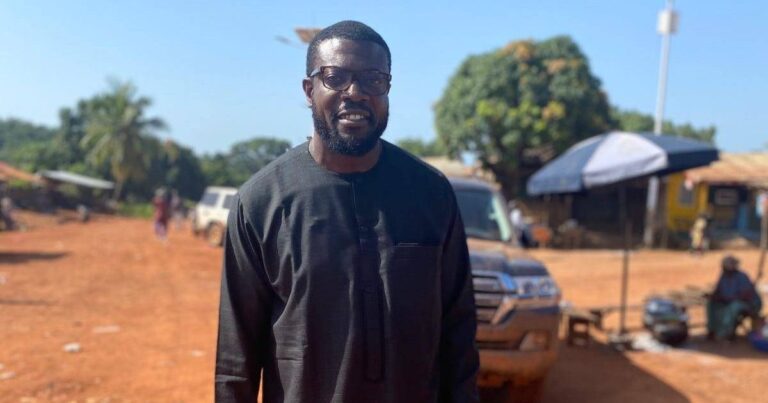

Guinea, United States, France: the three lives of Abdel Camara

He was born in Guinea, studied in the United States, moved to France. Abdel is at the same time, Guinean, American, maybe soon French, and also, muslim. So he knows a lot about what it means to "be black" in this world.