Chapter 1 – Happy birthday, Vannak

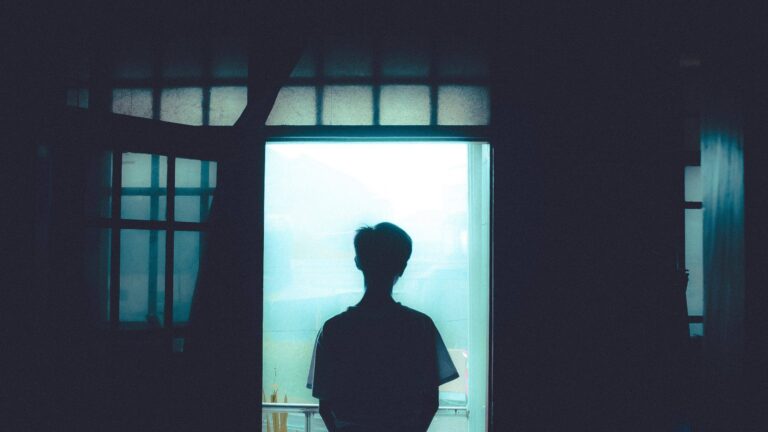

On the other side of my bedroom door, I can hear them conferring in low voices. Maybe I’m overreacting a bit. Unnecessary precautions. It’s fine that I don’t kiss them, but I could at least have had lunch with them. After all, it is my birthday.

It was my brother-in-law who came up with the idea to Facetime. Jules calls me and, at the end of my bed, I watch them dipping their spring rolls in sauce. Vientiane wanted to bring me something to eat in my room. The tone of my voice was rather curt. “No way. You put them in front of the door, you step back, and I take them.”

The cake, full of cream and shiny strawberries. The candles, flickering on my tiny screen. The traditional Happy Birthday, followed by my first name, Vannak. The excitement of the children. My sister’s thumbs up, the smiles. I kill the mood a bit by demanding no one blows on the cake for me, not my father, not even the children. Jules removes the lit candles one by one. We pretend everything is normal. They put carefully wrapped presents before my door. The whole family has gathered in the hallway. “Back up a little.” I’m trying to film myself tearing the plastic off the DVD ‘Diamond Island,’ the wonderful film by Davy Chou, which I went to see in Paris when it came out. Another surprise, a photo book about the temples of Angkor. Gifts to prepare me for my trip, hopefully in October, for the Water Festival.

When I retrieved my piece of cake in the doorway, I had the impression of being in one of those films where you see a prisoner seizing the bowl held out by his jailer.

*

It’s strange to stay cloistered in this room when the weather is so nice. I’m not the only one though. The whole of France might be locked up. There are rumors of a curfew.

The wallpaper is faded, my shelves are crowded with books and newspaper articles. At the place where I’ll move soon, the walls will be salmon-colored. I’ll have an office. I’ll buy an armchair at Ikea, with a lamp to read in the evening.

I’ve known this little room all my life. The view isn’t bad. The square seemed immense to me, as a kid. The grocery store, open until 10 pm, has changed owners several times. There are these guys in the shadows until dawn seemingly watching people come and go. A pharmacy at the end of the street where the owner was murdered just before closing one Saturday in November. It was my sister who convinced me to buy an apartment. I hadn’t really thought about it, but I couldn’t really picture myself, once my father had left, living all alone in a council apartment that was meant to house a family

Goodbye Val d’Oise, hello Seine-et-Marne. I’m going to live in a very pretty new town, surrounded by lakes. I laughed when I learned that there was a Tang Frères and a Paris Store. My sister told me: “If you finally find your soulmate, you’ll have all the schools five minutes away from your house!” Vientiane and Jules live in a big house in a nearby village. I’ll be able to see their kids more often. I’m relieved my father is going to live with them.

*

The president finally announced the lockdown of the entire population. No curfew but restrictions, travel permits, remote working.

This is the first time I dare to take sick leave. With the cough I have, I would surely be treated like a leper at the office! However, I don’t know if I have it, the virus, since they hardly test anyone. On TV, the doctors advise against cough syrup. Ventolin doesn’t calm me. I’m reduced to taking Doliprane, which they have started to ration. I feel a bit abandoned.

I’ve stopped listening to the radio, the TV. Too anxiety-provoking, too repetitive. Not much interests me anymore.

This discomfort in my chest is starting to worry me but I don’t tell my father about it, he is already alarmed by my uncontrollable cough. I would like to be a silent patient. But I cough, I spit, I blow my nose. I’ve only had asthma for a year. Until now, I’ve been in perfect health. The doctor says the asthma came because of the pollution.

Vientiane is texting me several times a day. I reassure her. She says she’ll come by and give me a thermometer. In the bedroom, I’m bored. I finally open the books I ordered on Amazon: Father Ponchaud’s story about the Khmer Rouge, ‘The life of Buddha’ by Thich Nat Hahn, the novel by Marguerite Duras set in Cambodia.

I took an interest in my parents’ country rather late. If it wasn’t for Charlotte, maybe I wouldn’t have been whipped into a frenzy of reading about Cambodia. It was just before the birth of Léa, my sister’s eldest daughter. I remember that first conversation with Charlotte in a tapas bar, among mutual friends. She was bombarding me with questions about Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge, Angkor Wat, but I was unable to answer with anything but generalities. I was stung to the quick. Back home, I surfed through the INA archives, I browsed dozens of articles. I wanted to be perfect for our second date. I tried to ask my father about his life during the Khmer Rouge era, about the family’s flight, the few months spent in a refugee camp. A brick wall. He had nothing to tell me. Not because he doesn’t remember or because he’s trying to hide things, but that’s the way it is — my father doesn’t like to talk. The little I know about those years, I owe it to older cousins, an aunt and an uncle, but my thirst for knowledge was never completely satisfied because they are stingy with details. Sometime later, Charlotte took me to see two plays, Cambodge me Voici (“Cambodia Here I Am”) and the Théâtre du Soleil, performed by artists from Cambodia in Khmer. And there I learned and understood quite a few things. I felt that I belonged to a history that had never been so clearly told to me before.

One of the books that moved me the most was Christian Mey’s L’Abnégation de ma Cambodgienne(“The Self-Sacrifice of my Cambodian Woman”), the true story of a young Khmer who grew up in the Atlantic Pyrenees. The child responds to humiliation with violence but ends up becoming strong through rugby. I cried. Maybe because his mother’s death reminded me of mine’s. Maybe also because I wasn’t really aware of what my parents had endured in France before. Their loneliness, their poverty. Not long ago, upon seeing Vientiane fixing one of my hems with her sewing machine, I suddenly remembered that my mother used to do sewing work when I was little, at night, for a man who would come to pick up the clothes just as we were leaving for school. The haunting sound comforted me. Apparently she did this for years, with the professional Singer sewing machine that Vientiane later learned to use.

Maybe I’m really going to die ? It’s getting harder and harder to breathe. But I don’t want to go to the hospital. I remember my mother in her room, her smile that was meant to reassure me, her hand in my hair. And that pungent smell that followed me for a long time. But no, I can’t die. It’s not in my plans. A few weeks ago, I was visiting apartments with my sister. Vientiane didn’t let herself be fooled by real estate agents. We found a three-room apartment with a nice balcony. Vientiane did not find any flaw with it, but when she demanded a discount, I was afraid it slip through my fingers. I could already picture myself living there, with geraniums, jasmine, maybe even an olive tree. The sales agreement signed, I returned twice, after work, to get to know the neighborhood. The RER station built on a pond, the swans, the ducks, the book box. My sister was happy for me. “I could bring you something to eat from time to time. I’ll make you lok lak rice, caramel pork.” Before Charlotte, I dated a different woman. It was the time when I’d moved back with my father, after I was laid off. I invited her to our place. When she saw the blocks of flats, the squatters in the lobby, she got scared. I guess that’s not why she left me, but after that I never dared to invite a girl to my house again.

No sleep all night. Too much trouble breathing. Terrible anxieties. I don’t know whether there is something wrong with my mind or with my body. I took some ventolin. I felt a little better, but it didn’t last. Fucking pollution. Fucking factory waste, fucking cars! Last summer’s heat wave nearly got me, the hand rail in the bus was so hot! My lungs were on fire.

I sit on my bed with the book about Angkor on my lap. This room must be a nest of germs. I want to air out the room but as soon as I stand up, I get dizzy. The square is closed. Nobody in the street. Every noon, with her certificate, my sister comes to drop off meals for my father and me. Under the same roof, we live separate lives. I only leave my room to go to the bathroom or the toilet. I warn my father in advance, so that he can leave. I am a grenade with its pin pulled.

I browse on Facebook. I can’t get interested in what people are saying, in their indignations, or their anxieties. I looked for Charlotte among my contacts. She doesn’t post much. I would like to tell her about this trip to Cambodia I’ll take at the end of the year. But what’s the point of writing to her? We’re no longer in contact since she met some guy and had a child.

I curl up over my painful lungs. Only the images in the book soothe me. I compare the prices of plane tickets. Singapore Airlines? Malaysian Airlines? China Airlines? The borders are more or less closed. No more planes are flying. It seems even pollution is decreasing. Before we were confined, I had found interesting prices at Sovann Voyage. Charlotte left to visit Angkor a few months after our encounter. She had suggested that we go together. I told her I wasn’t ready! I was such a fool! I was afraid I would be disappointed. Afraid it would be too late. I had heard that the Khmer soul was disappearing, that the country was being colonized by China, that Buddha had been replaced by the dollar. Charlotte had returned from Cambodia enchanted. She had brought me back a krama, the Khmer scarf, and a small wooden sculpture of the four-faced heads of the Bayon.

In Angkor, she had met a French tourist. It was with him that she had her child.

Chapitre 2 – Brotherhood

Now it’s really bad.

I can’t swallow anything. Too much pain in my chest, throat, head, everywhere. After my birthday, I could still cope, but now it’s unbearable. Now I have to call 15. But I can barely speak, and my father won’t be able to explain what’s wrong with me. Vientiane came over in a hurry. When she opens the door of my room, the lower part of her face is completely hidden by a krama. I can only see her worried eyes behind her glasses. She doesn’t comment on the mess, the wastepaper basket overflowing with snot-stained paper towels. She calls the medical emergency services. It rings in vain. She goes back to the living room to recharge her cell phone. I can hear her curse: “What if it was a heart attack! He would have time to die!” My father only heard the last word.

“Is he going to die?

“No, Dad, I was talking about something else. He needs to be examined by a doctor. I didn’t know he was in this state.”

By dint of continuously calling, she ends up getting the emergency operator. She runs into my room, puts the speakerphone on. A guy talks to me over the phone. An annoyed voice. Like we’re bothering him, almost. Vientiane holds the phone with one hand and presses the krama on her mouth with the other. The guy gets impatient. He doesn’t understand what I’m saying. The truth is, I can no longer speak, which is what my sister tells him to emphasize the seriousness of the situation. The guy tells us that the emergency room can’t move at the moment, that my breathing difficulties sound okay, that there’s a whole list of priority people. I hear the anger in my sister’s voice, I see it in her eyes, but she manages to control herself, always very polite.

“So?” my father asks.

“They won’t come.”

“It’s because of the address. This neighborhood has a bad reputation. Firefighters were mugged again last week.”

“No, they are just overwhelmed.”

“We should have moved a long time ago. The city wasn’t like this when we arrived.”

“You’re not going over this again.”

“I didn’t speak French in the ’80s. I didn’t know there were good and bad neighborhoods. I chose this district. I made the wrong choice. And now they don’t want to come and take care of my son.”

I hear everything from behind the door. I would like to tell my father to stop blaming himself, tell my sister that after all my condition is surely not so bad. I just need some medicine to help me breathe. I’m suffocating. I’m in pain. Holy shit, why is this happening to me?

“What sickens me,” my sister says suddenly, “is that every single MP is tested! We, in the suburbs, we can die.”

“Vannak! “She let out a little cry. I smile at her to try to lessen the effect I have on her. Do not cough, mask the pain. But my forehead is soaked. The sight of the krama on her mouth and nose makes me want to cry. She has three children. I don’t want her near me anymore. I motion to her to step back. She retreats into the living room. The emergency room answers after fifteen minutes. Fifteen minutes! Maybe that’s why they call it 15.

Vientiane no longer hides her anguish. The tone of her voice is more assertive. Perhaps she understood that her courtesy earlier was counterproductive.

Between two coughing fits, I hear her describe my condition to a woman (“Miss, he’s really not well.”) who agrees to watch me on video, via WhatsApp. The connection is good. Vientiane enters my room again, I can’t help but feel a little ashamed to be seen in the middle of my surrounding mess. The lady asks me questions me but no sound comes out of my mouth. Does she think I am faking it to get her attention? The lady in the emergency room is silent for a few seconds and then finally gives up: “I’ll send a team for you. I hope they won’t come for nothing.” I can tell Vientiane is both relieved and anxious. In the corridor, my father speaks in half Khmer, half French. He seems to be completely losing it, I’m worried about him. Vientiane can’t help but do a quick cleaning in my room, closes the door and waits with my father. Three hours later, they arrive as I’m at my worst. I’m suffocating, I’m suffocating, I feel like I’m being submerged under water.

Four men entirely covered in plastic, their faces protected by a mask. One of them examines me. I hear the word, “Respiratory distress,” then “We’re taking him,” and finally “Can you walk?”. We’re on the eleventh floor. The elevator works but it’s too small for a stretcher. They help me get up. I’m weak, I have so much trouble breathing that I need help to stand up. One of them explains to Vientiane and my father that they might keep me for a while and that visits will not be allowed.

Before we leave, I take one last look at the small wooden sculpture of the Bayon that Charlotte gave me. The neighbors’ doors open as we pass. I don’t like to be noticed. We have always been very discreet neighbors in our building. I imagine people freaking out. The virus is on our floor. They are afraid of being contaminated. That’s all I am now, a virus. It’s like I’ve been arrested for murder.

The men support me. They encourage me, they’re gentle. I would like to tell them that I’m sorry I disturbed them. When they lay me down in the truck, and put the oxygen mask on, I feel a little better.

Guys in diving suits in the deserted corridor. Nurses and orderlies with goggles, masks, caps. I end up in a room that has just been disinfected. I entirely undress. I am informed that my clothes will be destroyed. I put on the dehumanizing little gown. I learn to pee lying down, into a plastic container.

Radios, scans, blood tests, drip. I am exhausted.

Vientiane had the presence of mind to give me a charger. I send her reassuring and even a bit humorous text messages. The crazy thing is that I’m in the hospital where I was born. I tell this to a nurse’s aide, and her eyes crinkle, which I interpret as a smile since the lower part of her face is veiled by a mask. I decide that I will be an exemplary patient. I won’t complain. I will always be smiling, no matter what.

I am struck by the gentleness of these women surrounding me. They are professional, they do what they need to do, yet always with a sweet word. I don’t dare question them, for fear of being seen as a nuisance. I trust them. The doctor comes by to read the results, asks me questions that I answer with a nod. He looks particularly tired.

They hooked me up to a machine, those famous respirators they talk about on TV. The doctor calls my sister in front of me. He explains that he will try to transfer me to a hospital in Paris that has better machines. Here, they had seven state-of-the-art respirators, but they were requisitioned and installed in two Paris hospitals. By order of the government.

I’ve been tested. Bingo! At least there is no more doubt. I have the virus.

I turned down a TV. If I want to recover, I shouldn’t watch BFM.

Sometimes, a care assistant calls my sister with my cell phone. She talks to me on video via WhatsApp but I can’t respond back to her. I hope my father doesn’t see me with these pipes and electronic devices… I must look like a robot. My sister doesn’t talk for long so as not to bother the caregiver. She is careful not to ask me questions about my health. I guess the caregiver gives her a continuous report. She shows me a drawing made by Léa, her eldest daughter. Cats, rabbits, hearts, and “I love you Uncle” that brings a tear to my eye. To let my sister know that I’m glad she called, I raise my thumb, as if I were on Facebook.

A nurse brings me a plate of couscous that she warmed in the microwave. Women from the town, ordinary citizens, have decided to take turns to provide meals for the nursing staff and the patients. She helps me lean back on my pillow, frees me from my oxygen mask. I’m not very hungry but I eat a little. Thank God I haven’t lost my sense of taste and smell. This couscous is simply divine. I feel all the love of the women who cooked it at home. It’s not a dish from a restaurant, it’s a dish cooked in the kitchen of a family I don’t know. My Moroccan and Algerian friends made me laugh at school when they all swore with their hands on their hearts that the best couscous in the world was their mother’s! The kindness and fraternity I feel at this moment are a counterweight the disease. I will never forget these women who, thanks to their couscous, made me part of the family.

They gave me shots to ease the pain in my chest. This made me sleepy for part of the day. They laid me on my stomach. My mind floats, in midwater. I don’t know why, but I see pictures of the two of us — Vientiane and I — school pictures. She was proud to explain that her first name was the capital of Laos. My mother had explained to us that when they arrived in France, my parents had been rescued by a Laotian: it was him that had found a job for my father. When my sister was born, showing him their gratitude was a natural thing for them to do. But when I asked why we never heard of him, I understood that my parents, for some mysterious reasons, had ended up falling out with him.

To keep my spirits up, I try to visualize my new apartment. The seller told me I could buy the attic too and have it converted. I will then go from a three-room to a five-room apartment! Since I was a child, I’ve regularly had the same dream: I’m in our family apartment and I’m exploring each room when I suddenly discover a door. I feel a joy impossible to describe, between grace and illumination when, pushing the door, I discover a new room, unknown to all.

A burning sensation in my chest. To reject the oppression that overwhelms me a little more every day, I summon the past or the future. I want my spirit to be stronger than my suffering body.

I think about Charlotte. She told me that she was not a religious person but that she needed spirituality, nonetheless. According to her, the universe was governed by an order. The human skeleton, the shape of petals, the force of attraction, the circulation of ideas since the beginning of humanity. She said that every life is necessary. The bee of course, but also the wasp or that damn mosquito. Even someone who doesn’t find a meaning to one’s existence is there for something. She believed that all people are connected to each other without knowing it. She liked to tell me about her great-grandfather’s father, a teacher of the Third Republic who passed on his knowledge to generations of small farmers. She told me: “Sometimes, when I pass a stranger in the subway, I tell myself that his life would not be the same if his ancestor had not learned to read and write with my ancestor.” I remember saying to her, “So we’re all brothers, if I follow your reasoning.” She smiled, “Yes, I believe we are.” Charlotte offered me books on Orpheus and Pythagoras. She was interested in ancient Greece, Egypt, the Middle Ages. Time has passed and I regret not having read them. I miss her conversations.

Charlotte is right. The virus passes from hand to hand, mouth to mouth, nose to nose. The virus is evidence that we are all like brethren.

Chapitre 3 – The static journey

I’m suffocating.

I can hear the caregivers talking to each other. The doctor is harassing the Paris hospital to get me transferred. A nurse invites herself into the conversation. ” They took away our best ventilators. It’s so disgusting. And it’s our patients who are not being treated!” From what I understand, I’m not entitled to transfer to Paris because I’m not sick enough.

Another nurse speaks to me softly. I can’t see her face because her nose and mouth are masked, i can’t even see her eyes because her glasses steam up, but I’m touched by the profound softness of her voice.

I no longer have the energy to look at Facebook. Still, seeing the pictures of flowers and cats scrolling by would do me good.

I am drowning.

What day is it? What time is it? The caregivers are taking turns passing my sister or her husband to me. Vientiane says, “Your boss called to know how you’re doing.”

She calls me so often that she doesn’t know what to tell me. She tries not to let it show, but I feel that she refrains from crying, screaming her despair and rage. The caregiver has picked up the phone. I hear her saying nice things about me. Brave, kind. She adds: “We are appalled, miss! This is not normal! He is young! The director of the hospital called in person, but Paris still won’t take him in.”

Although my mind is foggy, I make good resolutions, as if it’s the New Year. Some people want to eat less, quit smoking. For me, if I make it through, I’ll drink some fine wine. A friend of mine made me taste sulphite-free wines from small producers he knew personally. He said, “You’ll see, it won’t make you sick.” Nothing ever had tasted so good. I will have champagne too, a good Ruinard to celebrate my return.

Why this delirium about wine? My mind goes where it wants, I don’t control it.

I’ll buy coffee beans and a machine to grind it. I’ll try to find a butcher and I’ll eat fine meat: Aubrac, Salers, Angus. Life is short, so I might as well enjoy the good things!

And then, I’ll sign up for dance classes at the Maison du Cambodge. Monkey dance, Peacock dance, here I come! Every other weekend, I will go to the provinces. Saint-Malo, Houlgate, Dinard, Dinand (I always get them mixed up), La Rochelle, Biarritz. And Marseille!

I’m 38 years old and I have never been to Marseille yet.

I will immerse myself in the classics. Homer, Dante, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Racine! I want to improve, to elevate myself, to discover beauty. I’d like to share my plans with Charlotte but I guess you don’t just waltz back into a mother’s life with a pipe in your mouth and an IV in your arm. If my mind could meet hers without going through the phone, the subway, the Internet…

I get intoxicated by my longings.

If only I could breathe.

There is someone who will love me when I get out of here. A woman who may not be the most beautiful, nor the youngest, but who loves to laugh, eat, drink, make love, who loves life. (Reminder to self: sign up on Tinder.)

Surrealistic vision. A nurse wrapped in a garbage bag. She explains to me that the long-awaited new gowns won’t arrive for a couple of days.

Air, please, I need air!

I have never had so many desires, so many projects. I’ve spent my life waiting. I rarely decided anything.

I’ll run away from the fools, the lecturers, the egocentrics. My best friends will be people I don’t know yet.

I will stop useless debates.

I will go into the unknown.

I will give books to Vientiane’s children.

To my sister, I will send trees.

I will leave my job that has never interested me.

If I could talk, I would tell the caregivers and nurses that I love them, that they are for me the quintessence of humanity.

When her three children were born, Vientiane told me that she’d been deeply moved by all the care she and her babies received from midwives, childcare workers, nurses.

I had never spent a night in the hospital before. All these people look after me as if I was the most important person in the world. They are not afraid of me, they never show that I could contaminate them. Yet I know they are lacking in everything. Their masks are distributed sparingly. They barely sleep. Some have to live apart from their loved ones for fear of infecting them. They do their work with a conscience that moves me. I am too tired, otherwise I would applaud them every night at eight o’clock, too.

I love you and if I could, I would kiss you.

I’ll read Rabelais. And then Casanova too. I’ll tackle James Joyce and Proust, Virginia Woolf and Malcolm Lowry, authors known for being challenging to read.

I will never bitch again.

I will be thankful for life.

I will take my father to Cambodia. I’ll pay him a five-star hotel.

I’ll take in a dog, a cat. I’ll learn music.

I will ask my father to tell me about his youth.

My finger’s on the call button. I wave to the nurse to turn the machine, full blast. I need oxygen! She gives me an apologetic look.

Is Charlotte still traveling as much now that she has a child? Before she left for Cambodia, she told me about her own way of traveling. She called it static travel. After exploring a site, she would return to the place that had impressed her the most, preferably in the early morning or at the end of the day, when there were fewer visitors. Then she would sit down. And she would gaze, breathe. She would soak up the place as if in osmosis with the elements. She wouldn’t take any photos or notes, she turned off her phone. She was content to observe, to be in the present.

In the Bayon, where the temple towers have four faces turned towards each of the four cardinal points, she touched the stone with her eyes, her fingers, her nose, her ears. One hour, two hours. Time no longer mattered. She told me that she experienced communion with the beings who had shaped this place. A leap through time. A spiritual journey. Tourists would arrive, alone or in small groups, and then disappear like shadows suddenly chased away by clouds. She remained in place. When she finally stood up and said goodbye to the Bayon, the temple was still present within her. When she returned to Paris, all she had to do was focus, and she would recall the harmony of those immense faces. Absorbed by the spiritual, she was able to transport herself to the places she loved, through thought. Charlotte assured me I would be able to do it too, if I really wanted to. As she spoke to me, I was enveloped by the sympathetic smile of the faces with their half-closed eyes. It felt like a dream where I was pushing a door open.

My hearing is much more acute now that I am confined in this hospital that is so quiet. When I look up, I see divers pushing plastic-covered men on stretchers or in wheelchairs. If my family saw me, with the pipes and the machines with their flickering numbers, they would shudder with horror. But I can’t see myself. I’m somewhere else. I’m traveling the world. Soon I will be at the foot of the Bayon.

In the corridor, the doctor does not hide his anger. The hospital in Paris doesn’t want to receive me now because my condition is considered too serious! A few days ago, I was not ill enough. The doctor explodes. “It’s not the virus that kills! It’s mismanagement! It’s the lack of foresight! It’s a shame.” Then, further away (but I still heard him), he seems to be talking about me: “This man has no connections in high places. Every day I hear that patients from other hospitals have been allocated the right respirators because someone made a phone call. I can’t take it anymore! I’m sick of it! I didn’t sign up for this!”

The very gentle nurse, the one whose eyes I can’t see, told me that I would be plunged into an artificial coma.

For how long? I couldn’t ask the question.

My sister was warned. We are waiting for her to call me before I fall asleep.

Vientiane’s voice. Behind her reassuring words and encouragement, piercing anguish. She tells me that she loves me. The situation must be critical if she dares say such a thing. In the family, we are modest. We never say those things to each other. Her “I love you” sounds like a goodbye.

A warm sensation spreads through my arm, my chest. The word “coma” reminds me of a man who was asleep on a bed for years, the object of a battle between his loved ones, some of whom wanted to unplug him, others who wanted to stop him from dying. Am I going to become a sleeping body too, just a body, with a mind gone wandering into an uncertain world? Before I fall asleep, I try and crack a joke. I ask the nurse if she has seen Hibernatus. But my voice sounds weird. I think my thoughts are no longer able to turn into words. She shakes her head, without telling me that only groans came out of my mouth. I hope that when I wake up, the world will be fixed.

Everything is blurry. I close my eyes. The voices fade away. I feel sick, want to throw up. My life has gone by too fast.

My eyes are closed but I feel like I can still see through my eyelids. My mind drifts along the hospital corridors, visits the other rooms and then leaves through an open window. The city is empty. Things are not comparable, but I think of Phnom Penh, which the Khmer Rouge had completely emptied of its inhabitants in 1975. I don’t know what product they injected in me — I’m high! As if I’m watching Google Earth, here I am in an area covered with grass and trees near the hospital. The tulips are in bloom and I must be the only one who knows it. Rabbits are frolicking in the grass.

Voices whispering near me bring me back to the room.

Time no longer exists. Even though I know I’m asleep, I feel like I’m alternating between wakefulness and sleep. I dream, and then I have nightmares.

The voices talk about me. There are too many medical terms, I don’t understand anything.

I can smell perfumes that belong to the nurses and caregivers. I can smell the meals they serve in the other rooms around, the coffee they give out in the morning. I can smell ether, I can smell death.

My sister’s voice on the phone. The voice of a nurse who speaks to her in a compassionate tone. “If he wakes up, the after-effects will be severe. He will never have the same life again.”

I go on with my journey. Bedrooms, tulips, rabbits. My drone does not fly very far. I wish I could have operated it till it reached the Latin Quarter. Rue Mouffetard. That’s where she lives with her husband and her child. Like everyone in France, Charlotte is stuck at home. Confined. What a strange word. I picture her looking out the window, slightly worried, before she resumes typing on her keyboard. Oh Charlotte, I wished I could have seen you one more time.

A flat voice. The voice of the nurse who was so kind to me.

“In an hour. I’m sorry. You’ll only be able to stay five minutes.”

Then a caregiver.

“His sister will come. Someone is taking care of the father, he fainted in the hallway.”

I feel her shadow over me. This time, Vientiane’s emotion is too overwhelming. She no longer hides her grief. She is overflowing with love and sadness.

“You’re going to join Mom. Give her a hug and tell her that we miss her. The children will grow up without you, but you will always be there with us, always with us. You’ll always be my little brother.”

My brother-in-law’s quavering voice is covered by my sister’s weeping.

I remember the small wooden statue of the Bayon in my room. Charlotte’s gift.

I travel, from apartment to house, I fly over mountains and oceans.

A door. I push it open. Under a cloudless sky, I discover temples with walls overgrown by vegetation.

The Bayon rises before me. I climb a few steps, alone. I contemplate the faces looking north, south, east and west.

I touch the stone. I sit down at the foot of one of the four-faced-towers.

The wind kisses my face.

Softness.

The faces seem to gently close their eyes.

© photo : J.-B. Phou