Chapter 1 – Wolfgang

1987. Wolfgang was born in Munich, München. This is where he grew up. In a bourgeois, uneventful, passionless family. He moves to Berlin in search of the big thrill. He’ll find it. At his expense.

The whistles scream, shrill. Silence = death. White letters on black rectangles. A string of bodies spread out on a December asphalt. These bodies, these bodies collapsed on the icy asphalt of a Berlin avenue say that they are irremovable. Nothing will make them go away. Absolutely nothing. They’re the actual state of emergency.

Whistles again. No eardrum can ignore that sound, nobody can pass one’s way nor get on with life after they’ve come across that — just like they did before, as if nothing had happened. The whistles haunt, voices arise from the Beyond. They are present, terribly present. The whistles haunt. The space, the entire space is theirs. They impose this: not being able to turn a deaf ear.

Or to look away.

A dark-haired girl with white triangles on her back is screaming as loud as she can in a strange wind instrument from prehistoric times. A bagpipe, in fact, and her breath tears the instrument apart. Her look is terrible. It cries out for vengeance. The siren announces the worst, an era of fear; it freezes the blood. The sound flies over the alignment of bodies, it floats in the air. Terrible too. It’s the end of a world we’re talking about here. An apocalypse. Both a radical anger and a terror.

And yet, him.

He moves forward, staggering between bodies invisible to his sight. Nothing touches him, nothing affects him, nothing challenges him. Sick people evicted = sick people murdered.

He’s sneaking around. Absent, absent to pain, rage, violence. Absent, just absent. The screams, the upright fists, the whistles glide over his skin. His skin is like an oil, nothing clings to it, nothing adheres to it.

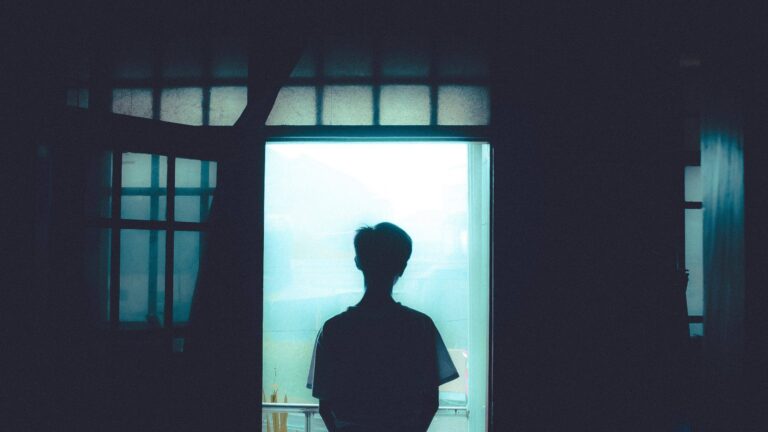

He wanders on the pavement between those human wrappings, magnetic to the asphalt. Neither dead nor alive.

He’s wandering around. One step, another. Glowing figure.

Still here and already elsewhere. He’s no longer a man, he’s a wraith.

*

1987. Wolfgang was born in Munich, München. This is where he grew up. In a bourgeois, uneventful, passionless family.

Industrial dad, stay-at-home mama, a depressed Schwester (sister), a Bruder (brother) as daft as a brush – and the guy wasn’t even sweeping up after himself !

First outbreak of pimples to the sound of the beautiful blue Danubefirst allergy attack the day after his first Beer Festival.

It was here, in this dull town where young men would put on their Versace shirts and Hugo Boss jeans and drink at the local pub and talk nonsense, that Wolfgang as a child, and then Wolfgang as a teenager, would desperately wonder whether the whole world breathed in such filthy boredom, such a banality as the atmosphere distilled by the Bavarian capital.

This question haunted his brain until his first trip, the year he turned seventeen. Modest, the guy dared the adventure as far as Ardèche before attempting the big jump the following summer via Thailand. Every day on his way home – a cozy little house that breathed boredom and the bullshit of the garden gnomes on the pavilion lawn – Wolfgang drove through much of this rich city. Rich, yes, clean of course, with a shimmering, bleached shine. Here, even the vans that served their Curry Wurst to passersby seemed to be coming out of a disinfected cold room.

It was also there, in Munich München, that Wolfgang listened to Kraftwerk, locked in his room as soon as he came home from school. There he would let himself slightly go to the sound of Radio Activity 3, all wrapped up in its timeless coldness… Those voices tampered with by various filters, electronic things that kept him away from humans.

Radioactivity

Is in the air for you and me

Radioactivity

Discovered by Madame Curie

Radioaktivität Fur dich und mich in All entsteht

When Wolfgang was haughty, sullen and lonely, when he put a No Future slogan on his torn T-shirt, it was not a style effect or even a fashion trend. The words came from deep in his gut, where his bitterness, fuelled by an endless grudge, was growing at breakneck speed. This city, this world, was definitely not for him. So…

*

Then one day… Precisely on his nineteenth birthday, Wolfgang took his backpack, a large bag that he used to roam the roads of the world, from the Ardèche gorges to Thai beaches.

When his mother asked him, “Why?” Wolfgang came up with the first thought that crossed his mind: “I don’t want to join the army. When you move to Berlin, you’re exempt.” That’s true. He’d read about it in a yellowed magazine. A newspaper that hung in the waiting room of a dentist of little talent – of course, the guy dreamed of being a cellist.

Berlin. This damned city, nicknamed in Munich the dustbin of Germany, needed above all to repopulate its almost deserted main arteries, an atmosphere bordering on ghostly. Hence this attractive offer to young people wishing to escape the unenviable fate of a life as a soldier. An alternative to all those who didn’t feel like singing:

You’re in the army now

Oh oh oh you’re in the army…

Now !

Berlin. A huge area “designed” to survive in the shadow of the wall that divided the city in two. Not to mention the French, English and American districts, you could only enter with a passport and the required nationality.

A lake, parks, a forest you would visit at your own risk: the probability of hitting THE wall hard at the end of a bucolic walk with picnic and all was not negligible.

On the other side, the eastern shadow, the gray city. Forbidden.

On the Kudamm, a large avenue bordered with a few movie theaters and somewhat silly fashion boutiques, the legendary department store KaDeWe set the tone just for its shop sign alone: Kaufhaus des Westens, Department Store of the West..

Its mission was clear.

Now, we liked to pretend as if it was nothing. For a few meters at least… because Berlin was still a ghost town.

A neon light with uncertain flickering… Decomposed silhouettes wandering from one bar to another in the opacity of this Berlin night. Opacity yes, because the lighting of streets, avenues, arteries was not supposed to weigh much in the municipal budget.

Saturated guitars, movement of bodies in electrified penumbra. Veiled laughter, masked in the no man’s land of the Potsdamer platz haunted by its gloomy past, surrounded by symbols of the ex-Gestapo. Far from the tasteless sweetness of Lake Wannsee, it was impossible to resist: just follow the call of this insomniac tempo.

*

By that time, in the west of the city, on this side of the wall, Wolfgang was working in a record shop. A weird weird place invaded by fluorescent sculptures, a place from which a raw, non-negotiable fury was escaping: Nina Hagen’s punk opera, Blixa Bargeld 5’s jackhammers, Nick Cave’s dark blues.

Settled in a rather clean and orderly squat – there lived young men from fine families, very polite under their Iroquois crest – Wolfgang had fun on full moon nights, and the others too, in boys’ or girls’ beds, depending on the mood, depending on the moment, and he loved it.

On his twentieth birthday, he made a phone call to Nihat, a handsome dark haired boy- lightning bolts sprang unexpectedly from the depth of his eyes. He offered him a few sexy frolics with shrudel and Bengal fires to celebrate his birthday.

The young Turk lived in the Turkish quarter, as it could be expected, two blocks from Wolfgang’s squat. But it was his sister who answered his call, and in a rather creepy voice.

“Nihat is sick. We can’t see him anymore. “

The intonation was closed, definitive. Irrevocable.

Yet the sister liked Wolfgang. Usually he made her laugh, smile or even shiver. Especially when he sang in her ear:

In Berlin, by the wall

It was very nice

Candlelight and Dubonnet on ice /

We were in a small cafe

You could hear the guitars play

It was very nice

Oh honey, it was paradise.

That day, no laughing, no smiling. A chill maybe, but not the kind that would make him want to go on.

Yet an hour later, Wolfgang decided to find out more. He crossed Potsdamer Platz and then the exotic Oranienstrasse, before rushing down the alley that led straight to the building where Nihat and his family lived.

There are streets that stink of death. Surely this was one of them.

*

Two weeks. The time he needed to decide whether to take the test. Or not.

Thinking about it, thinking about it again and again, especially alone: the idea of sharing this “thing” with someone didn’t cross his mind once. Alone, yes.

And then taking action. Appointment, choosing a day: what day, what time?

Take some blood. Finally the last round: waiting for the result.

The night before the test, because now there would be a night “before”, he dreamt of Nihat, and his sister too, staggering back and forth in a dark and deserted bar, yellowish light, to the distorted sound of Lou Reed’s Berlin . Lost in an echo. Nihat avoided his gaze, trying as he could to hide his face with a trembling hand. Berlin disappeared from the dream’s soundtrack and Nihat’s voice, cold, distant, sang: Berlin Nihat avoided his gaze, trying as he could to hide his face with a trembling hand. Berlin disappeared from the dream’s soundtrack and Nihat’s voice, cold, distant, sang: Berlin disparut de la BO du dream et la voix de Nihat, froide, distante, chantonna :

It’s so cold in Alaska

So cold in Alaska

It’s so cold…

Two weeks. Two weeks of worrying oneself sick. Going around in circles like a tiger in a cage or any animal species caught in the trap of human folly.

Up to this day, life was carefree, carelessness that flirted with a certain amount of morbidity, but still carelessness. The kind you recognize the day you walk out the door. Before that? You didn’t feel it, you didn’t think about it. It was there, light, and that was it. And that’s already something.

Two weeks!

On D-Day, the day he waited for and feared, the alarm clock rang at 8:30, and the least you could say is that it was not routine around here.

From the room next door, a pink-crested punk jumped on his rotten mattress and exclaimed, “What the hell is that?”

No sooner had he tried to draw the curtain than the light flowed freely through. Wolfgang immediately closed it all. Light was not welcome.

In the deserted kitchen of this sleepy house, he swallowed a bowl of coffee without sugar or milk, without toast, without anything.

Then he lingered in the bathroom, toothbrush in his left hand, toothpaste in his right hand. Staring aimlessly into the bottom of the sink.

The faucet ran on and on without the wasted water shocking his green conscience, so finely tuned through a multitude of daily habits.

An hour later, he took the ticket with only a number written upon it, to go to the doctor’s office. He crossed the city from Kreuzberg to the U Bahn Adenauer Platz, a place he was not used to, out of his reality. On a street corner, he was startled by his reflection in a shop window. He didn’t recognize himself, looking like a sleepwalker.

Arriving on the right street, at the right number, he checked the brass plate at the foot of the building and only thought: “This is the right place”. So he rang the right intercom. He was asked for his number, an “open sesame” that he could have done without, but it worked: the front door opened without delay. He crossed a first courtyard, then another. The doctor’s office was on the ground floor at the end of the second courtyard. A little hidden, a little otherworldly.

He waited in a waiting room, logically, the shared medical clinic was specialized in answering his question, his result. On the table, information leaflets, all of them alarming. On the wall a few posters to convey the message. Everyone was looking at them out of the corner of their eye, at an angle, never directly: Kein problem, I won’t need that. There were about ten of them there, all waiting in their chairs: seven men, three women. Each holding a little piece of paper with their number. Alone or accompanied, eyes lost in the void or fixed, magnetized towards the ground. An air of Russian roulette that dared not speak its name.

A door opened, his number was called. Dr. Angermüller, a redheaded woman in her fifties, let him in. She was wearing a flowery blouse with daisies and forget-me-nots, a print that was rather out of context. Dr. Angermüller gestured for him to sit, took his ticket and drew a simple sheet of paper from an envelope with the same number on it. Then she read it. She needed only a few seconds to raise her head and to say one sentence, just one, a few words ad vita aeternam tattooed on his brain: “This is a result that you would not wish to your worst enemy”. Wolfgang got up suddenly, turned around to avoid the doctor’s gaze. A few seconds as if Dr. Angermüller didn’t exist, no, nein, as if Dr. Angermüller had never existed.

Air, air, air. He rushed to the window which he tried in vain to open, again and again. The fucking window resisted his attempts for surprisingly long while. Stuck. But it was without counting on this incredible strength, something from elsewhere that Wolfgang discovered at that strange moment in the power of his arms. An unknown force. The thing, the window, finally gave in and opened onto an inner courtyard. Then time took on another color, another dimension. Another space. In fact, time stopped.

Opposite him, a woman was shaking a small ochre prayer mat out of another window, the one in the stairwell, to air it out. A fuchsia scarf covered her hair. She crossed his eyes, addressed him with a shy, puzzled smile. Haggard, Wolfgang observed this incongruous image, just like that, without turning away, without taking his eyes off it.

A prayer mat. After all, why not? From now on, anything would worth it.

Chapter 2 – Yaya

This morning, Yaya read this news. First without really believing it, then by allowing oneself to think that, yes, existence could bring good news.

2015. Dubreka, Guinea, 17 August: As of 10 August 2015, it has been five days since the country has notified any new cases. In order to maintain the goal of zero cases, the WHO, through its social mobilization and engagement teams deployed in the prefectures, is emphasizing communities’ involvement, which is the main guarantee of reaching the goal of zero Ebola cases.

Five days? This morning, Yaya read this dispatch. First without really believing it, then allowing himself to think that: yes, existence could also bring good news. Five days, five weeks, five months. Five months since he arrived here in Hauptstadt 8 Berlin. Yaya lived in Mitte. Literally: the middle, the center. For the neighborhood had been, long, long ago, the trendy place to live. Long before the Wall made it the grim, first vision of the East, when those from the West left the subway, with its terrible armed checkpoint, to spend twelve hours – no more – on this side of the border. Wilkommen in die Deutsche Demokratische Republik But that was before.

The first time Yaya arrived here, in Berlin Mitte, he was far from imagining a place with a long and heavy history. Here, elsewhere? It didn’t matter. Above all, he felt very far from Dubreka, at the bottom of the Smoking Dog Mountain, where he threw himself into the Bondabon waterfalls as a teenager. Where he tasted a rare commodity – books traded on the black market – that made him dream and think.

Even today, now living in the Berlin Mitte, everything around him signified that distance, at every moment. The faces, and above all the way the bodies moved, the smells, what people ate, their words, their silence.

Yaya had arrived in the middle of winter, a winter that overshadowed everything else. The cold eliminated feelings, all views of places, people, life. That’s all there was, the cold, nothing else. A daily struggle. That icy breath that gripped the body, the whole body, when Yaya came out of that old building overheated with coal, to dare to face that icy wind.

His departure from Guinea was long thought out and prepared.

Yaya had not contracted the virus. At least, he had shown no signs of it. Luck, fate or injustice, who knows. He was the only survivor among his five lost sisters. Dead. Yaya was a living miracle, something strange, with no explanation. What is it to be alive when death has broken everything, stolen everything, so close to you? And then Yaya lost his job, and then his friends – except for young El Hadj, a long, thin boy with a pinhead who rapped under the handle of Hajji as if to exorcise his world. From morning to night, El Hadji walked along roads, squares and alleys, drowning in waves of syllables and spitting rhymes, in a nervous flow until he lost his breath. Until he couldn’t take it anymore.

His words invaded the space. They bordered on the infinite. Strange chanting.

El Hadj Hadji was the only person around who didn’t flee from Yaya. Everyone else was afraid. Fear of being contaminated. Panic in the air in the air.

When they saw Yaya coming home from work or from the market, the neighbours would quickly barricade themselves in. Yaya lost his job, but he hung on and wanted to open a shop. However, no customers ventured to visit him.

Deserted, the shop. Fear drives you crazy, that’s how it is. Fear excludes, and it reassures people. As a result, Yaya says to himself: “Since you escaped death, go live your life elsewhere. What’s the worst thing that could happen to you? »

So the young pinheaded rapper, El Hadj Hadji, helped him to raise the cash for this long journey, a tricky task. He helped him organize everything to prepare for his departure.

And a few months later, Yaya found himself here, in the icy winter of Berlin Mitte, la Hauptstadt du Deutschland.

*

One day and a birthday, just one year after his arrival, Yaya read a small ad in Zitty, the famous alternative and cultural magazine.

Berlin, Shöneberg. Seeking roommate, nice independent room. Shared kitchen, bathroom and living room, very low rent. Other cultures welcome.

Since the development of the AFD (Alternative For Germany), many have been keen to publicly differentiate themselves from this sinister trend. A gesture that was certainly gratuitous, purely demonstrative: the troop of cheap Nazis was not recruiting from Zitty’s readers. But the intention was there and Yaya appreciated the symbol.

Shöneberg was a nice place, quite charming. And this proposal could give him the opportunity to escape from community gatherings, turning after a while into something oppressive – however warm they may be.

He showed up at the address given during the quick but friendly phone call he had made to the advertiser the day before. The guy opened the door for him, smiling. He was in his fifties, the face of a guy who must have seen a lot of hardship, but who, Hamdullah,had done quite well.

He invited him to sit down and offered him a beer. Yaya accepted, even though the slightly bitter taste of the yellowish liquid that was flowing in the local bars wasn’t really his cup of tea.

So the guy introduced himself.

– My name is Wolfgang. I’ve lived in Berlin since I was nineteen. Before that I was in Munich. I grew up there. Do you know it?

– No, don’t know.

– It’s okay, you didn’t miss anything.

*

Yaya moved in with Wolfgang a week later.

The two men learned to discover each other, slowly, without forcing things. Sometimes they cooked together, Yaya loved schnitzel, those thin breaded cutlets served with red cabbage and potatoes.

Since his arrival in Berlin, he was immersing himself in novels and short stories. An avid reader. Wolfgang showed him his collection of vinyls, which he loved to crack under the diamond of his turntable while contemplating legendary album covers.

Wolfgang wanted to know more about Yaya’s country without wanting to riddle him with questions. He had noticed that the evocation of that time was difficult, even painful. So he was at pains to be discreet.

One night, he browsed the Web. No problem finding Dubreka, the Mount of the Smoking Dog and the Bondabon waterfalls that Yaya evoked with a luminous smile, a real smile at last. The photos made you dream.

But in the article just below, the news was turning into a nightmare. One name, one word ranged from testimonials to scientific contributions. Ebola.

Figures, gloomy facts that reminded him of the worst. Especially when he read the story of Mariame. The young woman recounted her illness and concluded with these words: “I wouldn’t wish this thing on my worst enemy.

The terrible memory of Dr. Angermüller came and blew an icy air right there in the corner of his ear and stayed for a while, floating in the room, before finally evaporating into the air.

*

One night, one evening, they told each other everything.

Yaya had just met a woman who made him dream, to the point of humming soul tunes in his head that caressed his soul. To give this story a little chance, a chance for a future, he needed to say, it had to come out of him, from where everything was buried, there, there, in those inaccessible depths. Wolfgang had rebuilt himself from bits and pieces, also in silence.

Those dead, those stained faces, those emaciated, blinded bodies. Drained of their substance. Fleshless bodies.

Wolfgang, a vision came back to him, just like that, just by telling Yaya. As if it was yesterday. His first hospital appointment. The waiting, the waiting, hours. Finally, a nurse took him to another place dedicated to another wait, a kind of small salon away from the world. And that’s when he saw her. A floating, wandering form, all lost in a pastel dressing gown – such a light blue mixed with a pale mauve tonality, of a strange softness. No face, no arms, no hands, you couldn’t tell; just a fluidity that rippled between the walls. A di sintegrating life. A vanished soul.

And then there was the time of anger.

The whistles scream, shrill. Silence = death. White letters on black rectangles. A string of bodies spread out on a December asphalt. These bodies, these bodies collapsed on the icy asphalt of a Berlin avenue say that they are irremovable. Nothing will make them go away. Nothing, absolutely nothing. They’re the states of emergency.

Wolfgang remained a spectator. Too lonely, too weak, too thin. Already between two worlds. One day in December, just before he tried his first tritherapy, he came across the screams and fury that were roaming the asphalt.

He moves forward, staggering between bodies he can’t see / invisible to his sigh, invisible to his gaze. Nothing touches him, nothing affects, nothing challenges him. Absent to pain, rage, violence. Absent, just absent. His skin is like an oil, nothing clings to it, nothing adheres to it. Still there, and already elsewhere.

Yaya, for his part, told of the bodies that were emptying, purging, expelling, burning, burned with fever. The corpses, their smell. The ordeal of his sisters, the youngest was twelve years old. Twelve years old… Absurd: staying here, alive, going on without being shattered. Moving on? Going through death as one goes through life.

And he’s wandering around. One step, another. Glowing figure. He’s no longer a man, he’s a spectre.

Since we couldn’t say and above all hear everything – nobody could do that – Wolfgang and Yaya took a notebook to write down yesterday’s things. They gave it a name. Epidemics..

A dark tale, survivors’ diary.

To their words, to their stories, they added others that they collected from the libraries of misfortune, the stories of misfortunes and struggles.

Yaya opened a page, randomly.

We wash our hands, we make people take their temperature. That’s the price of passage. I’m going past all the posters: drawings of dying patients. I meet my friends in class. Platonic greetings, no more hugs and kisses. Ebola’s on the prowl. Facinet Kabele Camara, An unwanted companion

Another book, another page.

All his friends are terrified, says Mr. Michaels. They’re terrified that he gave it to them and now they’re going to get polio too. Their parents are in a state of shock. Nobody knows what to do. What can we do? What should we do? What should we have done? Phillip Roth, Némésis

Wolfgang was watching the night from the living room window. Yaya continued his reading.

The sun was bright. The slightest dirty water started to smoke. The days were hot, the nights cold. There was a case of cholera, a devastating one. The sick man was swept away in less than two hours. The convulsions, the agony, preceded by cyanosis and a dreadful cold of the flesh made the emptiness around him. Even those who came to help him retreated. Jean Giono, The Hussar on the Roof

Yaya lay down on the floor and declaimed almost silently. A whisper.

Without memory and without hope, they settled in the present. In truth, everything became present to them. It must be said, the plague had taken away the power of love and even friendship from everyone. For love requires a little future, and there were only moments left for us. Albert Camus, The Plague

And then they went out to look at the snowy life under that long winter, as it was before. Almost light. Almost carefree. Life.

Chapter 3 – El Hadj Hadji

Soon the first assessment is extended to 45 contaminated and two dead. In the days that follow, the theme becomes a little bit ingrained, but nobody really believes in it. China is far away. And yet… a doubt creeps into the atmosphere. An interrogation.

1 January 2020. Paris.

Between two deliveries, Hadji tries to reach his buddy Yaya, the Berliner. The courier, of course, again and again.

Hey buddy was machst du denn ? (what are you doing ?) You see, I’m making progress, huh. That’s because I’m getting ready to visit you ! I’m just waiting for spring, so I don’t freeze on the spot. So you had a good New Year’s Eve? 2020, we’re here! I’m telling you, this one is definitely our year.

El Hadj Hadji arrived in Paname six months ago, after multiple and terrible adventures he tells the stories in his raps declaimed at nightfall on the steps of the Sacred Heart.

I’ve travelled the lands, and the deserts and the mountains and the shores and the forests and the countryside…

When I arrived everything hit me

Around my furnished room between Barbès and Rochechouart

I’m not wood I’m not stone

I’m made of blood flesh of blood muscles of prayer desires…

Since then, he has been walking the streets of the city, eyes wide open so as not to lose an iota of these urban visions. While waiting for something better, he found the job that allows him to discover unknown streets and neighborhoods. And he loves it, despite the stress of one delivery after another: he’s now a delivery boy at Deliveroo. The guy carries burgers, sushi, pizzas, risottos, mafés, salads, poké bowls, whatever. He rides, he rides.

11:00 p.m., exhausted, he goes home. Shower, sandwich, he sprawls onto his sofa bed. Eyes half open, he catches the remote control, presses a random button, the ad, and then another button.

Yesterday, 31 December 2019, Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist at Wuhan Central Hospital, alerted his colleagues to the discovery of a mysterious illness. Resurgence of the SRAS? Doubt persists. As of today, the World Health Organization is informed of several cases of pneumonia like disease in Wuhan.

Midnight. Hajji El Hajj is going into sleep.

January 7, France Info. Chinese authorities link the symptoms of the mysterious cases of pneumonia-like symptoms that are increasing in the Wuhan region to the discovery of a seventh type of coronavirus. The possible link back to SRAS is now closed.

– What’s up, man? Do you ever call back?

January 18th. The first assessment is extended to 45 contaminated and two deaths. Symptoms suggest acute respiratory infections but also more severe forms that can lead to death in frail or elderly patients.

— Hadji, brother, sorry, I had a problem with my SIM card… So, tell me, how’s life?

— Life rolls on. I’m the one running after it.

— You got a problem?

— No, but you know, it’s not easy. I love Paris, yes, it’s a real whirlwind. But you just have to make a place for yourself. Wherever you go, nobody’s waiting around for you.

— Hey, brother, after all we’ve been through, you’re gonna make your place. Don’t forget, we’re survivors.

— Survivors, yeah, for sure. Now, personally… I just want to be a living one.

Soon the first assessment is extended to 45 contaminated and two dead. In the days that follow, the theme becomes a little bit ingrained, but nobody really believes in it. China is far away. And yet… a doubt creeps into the atmosphere. An interrogation.

The same evening, Hadji El Hadj starts writing a new text. Paper, pencils, the old-fashioned way. It takes place in the notebook. I just want to be a living one.

The next day, he gets back on his bike. And El Hadj rides, rides, rides.

He zips from one street to the other.

March 17th BFM. Contaminations in France progress inexorably, with 175 deaths. 2,579 patients are hospitalized, 699 of whom are in intensive care. France, after Spain and Italy, entered general confinement on Tuesday lunchtime. The French can no longer leave their homes, and if they do so, they risk being fined.

And El Hadj rides, rides, rides.

April 12th.

— Hello, it’s Deliveroo.

— Let me open for you, it’s on the third floor, door 35. I left a tip in front of the door, you can drop the package off, thank you.

The door to the hall opens. Deserted, of course, it’s like everywhere else. Hajji El Hadj takes the elevator. He has no mask, no gloves, so he improvises: he places a small piece of paper between his finger and the floor button. He holds his breath, he doesn’t know if it’s of any use, but when in doubt, he doesn’t breathe. When he reaches the third floor, he walks towards apartment 35, drops the package, takes the two euros left for him. Gets ready to turn around.

But then he hears a voice, almost a breath, on the other side of the door. A woman’s voice. The wall is thick, or the voice is too weak, he doesn’t know. Hajji has a little trouble understanding his words. So he listens.

— What’s your name?

— El Hadj.

— That’s nice. And where’s that from?

— I’m from Guinea.

He brings his face even closer to the door, until he brushes against the material. Breathe in that presence.

— I’m Sandra.

— Are you all right, ma’am?

— I don’t know, I guess. What day is it?

— It’s Thursday, April 12th.

— April 12th… So that’s it, yes, that’s it. It’s my birthday. I’m sixty today.

— Is that right? Happy birthday, then.

— Thank you. Thank you. You have a nice voice. It’s been good talking to you.

— Me too, ma’am, it felt good.

— Sandra, call me Sandra.

— Happy birthday, Sandra.

— Thank you. Thank you. And above all, take care of yourself. Be, be alive.

Once out of the building, El Hadj Hadji gets back on his bike, crosses this deserted Paris. So he rides, rides, rides.

Goes up the Champs Elysées, arrives at Place de l’Étoile. Just in the centre, facing the Arc de Triomphe, stop, he stops. He keeps the moment frozen, contemplates the apocalypse.

And he makes a promise to himself, first whispered, then declared as loud as he can, right there at the crossroads of those famous avenues. Two sentences, like an echo, they cross the city.

“April 12, 2020, it’s 8:00 p.m., this year will be ours.

And I’ll just be alive.”

You were born. And so you’re free. So happy Birthday.