Last year I read an extraordinary book by Doris Lessing: Memoirs of a Survivor. A book that left me reeling. The plot, divided in two, is set in a society that is in decline. The narrator participates and observes the world from her window, as the civilization outside collapses. A world that is falling, crumbling. Life is worthless. Only a part of the population will be able to survive.

Now, when I go out to do my daily shopping I feel like a sort of survivor. Like Lessing’s storyteller I go through an almost metaphysical experience: descending on my brief 15-storey journey to the street in this time of pandemic.

In front of each closed door, the shoes of its inhabitants await. There are those who leave only one pair and others several. From a lofty floor high in the building, I work my way down these steep stairs . Descent to that dreaded hell: the street. Where fear rules because it has become a dangerous abyss. The world walks on its tiptoes. Men and women with masks but who aren’t superheroes. Mouths covered, words are only whispered in the streets and public places. Empty beds waiting for future patients. A post-war climate reigns in the world. Those over 70 will have to stay home for good. The world is now being united by a common enemy, a small virus with a crown. Many bodies fall and, as in many Greek tragedies, some won’t even have a tomb.

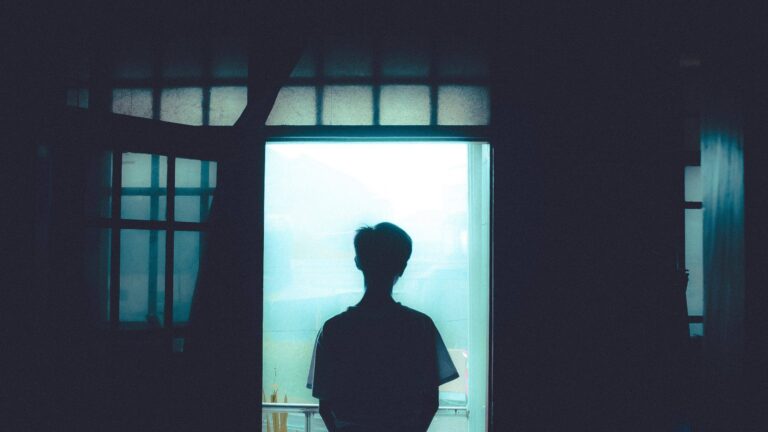

I pass each floor, slowly. Some are without light, others with a spectral blue light. Evocations bloom out of the obscurity, each floor inspires its own kind of shadow theatre.

First stop, the form of a Minaret looms out of the crepuscular light, with its call to prayer distant at first, then growing. The voice echoes from mosque to mosque. From the tower, the muezzin calls the faithful, his cries uniting the people, a thread of prayers stretching across the sky as the sun rises, filling my eyes with light.

Shoes are left at the entrance of each temple. To penetrate, one must be barefoot. The house, during this time of plague, has become the sacred place, sacratus, the place you are devoted to and a place also — according to the etymology — of sacrifice. Women and children live scenes of irreparable violence. Freedom has been sullied. A megaphone announces every night you have to stay at home. Outside the enemy prowls; the Covid19 like a Minotaur or a new Medusa, a plague let loose upon the 21st century. And at 9 p.m. sharp, people stand at their windows and applaud.

Those who strive to develop a vaccine are the new Theseus and Perseus. Theseus, using the gullible Ariadne, managed to kill the Minotaur that sowed terror in Crete. And Perseus, misinformed, went out to cut off Medusa’s head aided by nymphs and gods offering helmets and winged sandals. The Minotaur and Medusa were defeated. The bloodshed continued anyway.

On the eighth floor an amber glow beckons, and a door is ajar. Crossing that threshold would be like traversing the columns of Hercules. An open door is always an invitation but it is also a limit, beyond which the poor Ulysses — the one from Dante’s Comedy finds himself thrown into hell, — punished — forever — for not wanting to stay at home.

Those who stayed at home were saved from evil. The evil of temptation, the evil of wanting to experience life.

In A Journal of the Plague Year, Daniel Defoe narrates the plague that struck England and the whole world in 1665. He tells of the desperation of men, women, children and old people, none of whom could go beyond the door of their house after sunset. The plague was multiplying and hundreds of people were dying every day. The young protagonist decides to travel, he has no fear because he believes in God’s protection. He read the Vulgate and there among those pages he feels the demonstration of his destiny, his good fortune. All the while, he affirms that he cannot get sick or he’ll automatically become the object of suspicion… Evil is in you, you become a carrier of Evil, which is Evil. The whole of London was crying, the narrator tells us firmly. The plague wiped out a hundred thousand souls, the character signs at the end of the text, thus asserting that he has been saved. But not from the horror.

Two floors are in darkness. My heart beats like the rhythm of an African drum. Every door hides something sinister, some handles and latches have been laced with white and others with red. There is no noise, no music, no voices. The usual neighbours have disappeared. The feeling is that the city was devoured by a great silence. Nothing, not a single sound, everything seems to be suspended like in a scene from Goya’s dark paintings. I imagine deformed heads, parents devouring their children, two women and a man, a witches’ Sabbath, old men eating each others’ remains from the almost empty cupboards.

In 2003 I stayed a few months in Buenos Aires. Meanwhile in France, twenty thousand people died, old people. It wasn’t the plague, it was the heat, the climate change surprising fragile beings, without much strength, they were falling down like flies swollen by the elevated, extreme temperature. Morgues were saturated. In New York less than a month ago, they created trucks that function as mobile morgues. In Ecuador I saw how they set fire to the bodies in the streets.

Turn on some lights, I’m getting to the mezzanine. From high windows contrasting with walls of stonework, you can see the river. It could be likened to the Seine bursting into the Louvre’s vast halls. Were the palace stairs not covered with blood at the time of the religious wars? Catholic blood and the blood of Huguenots flooded the streets of Paris. The shadow of St Bartholomew’s can still be felt, the massacre of 1572 like a wandering ghost seeking refuge. The screams of pain are recorded by the poets in their pages and stories. Exaltations, Court of Miracles. From the tower in which Nerval hung himself, El desdichado peeps out, and as I squint my eyes I can imagine the wailing and suffering invading every corner of the city. Even on the cobblestones there are traces of old, past blood. Blood that resists disappearing and that persists in the energy, in the vitality, in the creative entrails of our lady, Paris.

I return to the Louvre and my gaze is lost in Poussin’s The Plague of Azoth, painted between 1630-1631. Poussin depicts a group of men who are going towards the impossible, salvation. No one can run away. Terror and desolation are etched on the static faces while rats run over the dead bodies. Poussin, in order to portray the plague that punished the Philistines for seven months, was inspired by the Bible — by the book of Samuel — and by the plague that devastated Milan in 1630. The aptly named black plague. “Fear the gods, fear the divine punishments,” say the vulnerable faces whose pestilence transcends the canvas. We do not come out unscathed when we enter a work of art. In Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, the body of a dead person is transformed into a source of information. Under Tulp’s expert supervision, a group of surgeons study the musculature of an arm. The idea is to dissect a criminal who died on the gallows, and whose body now serves science and without knowing it, also enters the history of art. Anatomy lessons were held in large theatres and some people paid to go on stage as models. Such are bodies, matter destined to decompose, drawing their sacred nature from this ephemeral and corruptible state. Rembrandt, the great Dutch baroque master, in 1632 captured the scene as if it were a photograph, the moment of the click in front of which faces and expressions have been frozen, suspended. We know that the body will shortly disappear. Such is matter. Around the same time and also in Holland, Baruch Spinoza, in his Ethics — Part III, proclaims “no one has yet determined what a body can do”. Centuries later, the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, replies “Spinoza tries to show that the body surpasses the knowledge that one has of it, and that thought surpasses in the same measure the consciousness that one has of it”.

Could it be that the presence of illness creates awareness of the body? In a very dark place I stop, my heart racing. I am a little of each of the characters that accompany me as I pass these fifteen floors. I am invaded by the fragility of this journey, transfixed by Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations on death, yet totally present in the moment. This instant of present like an elemental particle.

Fear can be lived variously, neutralized, managed, annulled, but it will materialize in one way or another. The door opens onto the desolate street of Palermo, this neighborhood of Buenos Aires. Only bicycles ridden by masked delivery guys, and beggars who have nowhere to take refuge. A few people carry shopping bags. The cartoneros have disappeared. The police spend their time conducting checks.

In the distance I think I can hear the bronze bells announcing the passage of plague victims from the Middle Ages. Or maybe it’s that famous verse of John Donne whose bell tolls in our collective memory.