He had declared war on the flies.

For some time, they had been invading his studio. He counted them regularly, the majority settled on his white curtains. None in the bathroom; clearly they were coming from the kitchen. His total had risen as high as 25. A record. He was preoccupied with their extermination.

He had bought a contraption that looked like a space heater, but was really a sort of giant toaster that radiated blue light. With each toasted fly, the machine let out a clack that made me jump and set my heart pounding. He counted the cadavers, but worried that the trap would attract a ladybird, or worse, a bee. I had seen him save a bee, one summer afternoon, that had crashed into his sink. He had given it a few drops of sugar water, and it had drunk, regained its strength almost instantly, and flown away. He had said that it was the best day of his life. It was one of the many times he made me laugh.

He had taken the killer space heater down to the basement and gone back to the good old fashioned fly swat. Concentrated, precise, he eliminated the flies one by one with a single slap. But he couldn’t let their presence go; it disturbed him, upset him, possessed him. He thought about a carnivorous plant, but the idea scared him too. The fact that they swallow and digest their prey repulsed him, and what if it caught a ladybird? I had said no to flypaper, worried that my hair would get stuck to it. He had ended up getting out the vacuum cleaner and had sucked up the little insects one by one. He had cleaned the sink, flushed the pipes with chemicals and set glasses over the drains. The flies had disappeared. It had taken him the better part of a week, but he had won the war. He calmed down for a while.

For some time, they had been invading his studio. He counted them regularly, the majority settled on his white curtains. None in the bathroom; clearly they were coming from the kitchen. His total had risen as high as 25. A record. He was preoccupied with their extermination. I loved watching him dance. He swayed to the rhythm, unfolded his limbs to jazz melodies with suppleness, elegance and restraint. A few steps back, eyes closed, his long eyelashes like a caress, in his red and black apartment: burgundy carpet, plaster walls painted red, black sheets, black furniture, black piano. He wasn’t handsome, but he radiated a charm in the literal sense of the word, a magic, an enchantment. I was often caught up in it, but I kept my cool – our relationship was more spiritual, cerebral. Our exchanges were often funny, complicit, light, although we ourselves were none of those things. Our interactions had been tender at first, and the tenderness remained. Then they became sensual, caressing. It had taken time, but it was another element to play with in our relationship.

The flies had come back, more of them than ever. Their presence seemed to extend to the whole neighbourhood. He spotted them everywhere he went – bars, restaurants, cinemas, every ceiling was colonised. He counted them methodically, looked for information online, trawled through expert forums and let the caretaker of his building know, in vain. He had ordered a sophisticated racket, the kind that electrocutes the insects, and played a vigorous game of squash each day. The flies upset him; he was barely eating and had started to lose weight. I was used only vaguely worried, used to his eccentricities. We saw each other regularly and we messaged each other every day. I loved him tenderly. He had the manners of a cat: he slept and walked noiselessly, amused himself by making me jump when I was concentrating on cooking. His wrists and ankles were delicate, his movements were gentle, and his bearing elegant. A cherished, bourgeois cat, who always seemed to be in the midst of some kind of lofty contemplation. And who, while dreaming of being O’Malley, was unfortunately far too fragile for the adventures he aspired to.

In his mind, everyone had a fly problem, and he thought it was the beginning of an invasion. He spent more and more time documenting the flies, contacting the mayor of his area, knocking at his neighbours’ doors to ask about their pest issues. He had gotten his war machine out again and sent me a message each night with the tally of insects killed. The subject had gradually taken over our conversations. The flies had become a kind of in-joke that added to our complicity: I thought it was amusing and made fun of his daily reports. I ignored the prickle of discomfort up my spine, used to him giving me that feeling.

Still, over time, I struggled to communicate with him. Our messages took on an informative tone – just his daily tally, a few numbers sent through without ceremony. I wasn’t happy; his sudden coldness bruised my ego. I clung to the figures all the same, these flies that kept me connected to him. We no longer managed to see each other; he refused my invitations and barely responded to my messages. At my insistence, though, he finally agreed to come to my house one night to celebrate a writing assignment that I had picked up thanks to him.

As soon as he set foot in my living room, an uneasiness set in. He was preoccupied, haggard. Normally, when he came over, he rarely sat still – from the couch to the window, from the kitchen table to the dining table, he wandered through my space, like a warlord through their conquered territory. Casually, he touched things, opened my books, my notepads, inspected the trappings of my daily life. It was only after drinking a few glasses of red wine that he allowed himself to rest and stretched out on my couch, inviting me in to be wrapped in his arms. I was a prisoner of war, but I was lucky, my captor was magnanimous.

It was the game that we played, the ballet that we danced: off-balance and uncomfortable, fuelled with risks and strategies, it was about who could hold out the longest. I only feigned a feeble resistance, because we both knew that the dice were loaded: the fight was his to win.

That evening, he was frozen on my couch, his body hunched. Uneasy, I talked non-stop, poured us drinks, busied myself in the kitchen. My movements were clumsy and my voice unsure. I fought to fill the space, dispel the emptiness between us and reach him once again. I could see him trying to react to what I was saying, making a vague comment, giving a little laugh at my attempts at humour… he was struggling too. The effort that we were both making only added to our discomfort. It made me sad; we clinked our glasses joylessly. Then, in desperation, I asked him about the flies, and he came to life. He explained what he had learned in his pest research and spared no detail that he had learned about the species. His gestures became expansive, his voice loud, he whose restraint I normally found so charming. He got up and mechanically paced the length of my living room, abandoning his meal and even his glass of wine. I drank for the two of us, both dumbfounded and moved. I had imagined the evening as a reunion, or perhaps as a separation, but I never suspected that it could take this strange, uncomfortable turn.

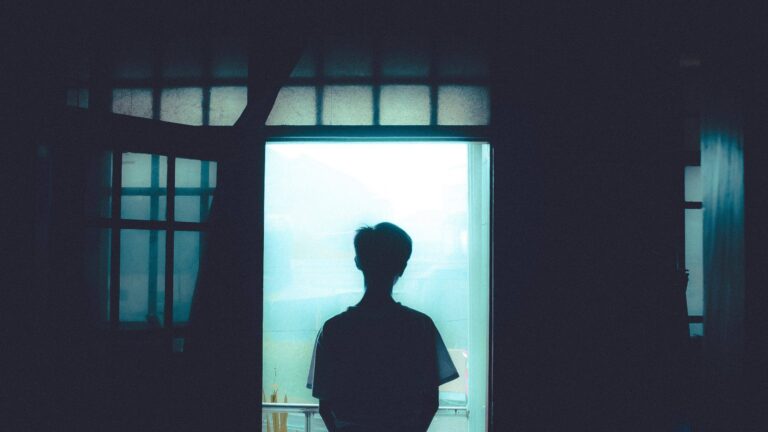

“They’re in here too! I can see them!” He stopped short and started to swat the air in front of his face. His movements were wild, his face contorted, afraid. There were no flies. I got up and wrapped my arms around his waist. I breathed calmly against him, his back pressed firmly against my chest. His arms stopped flailing. “They’re gone,” he murmured, lowering his head, his lips close to mine. “I’m tired,” he added, and I thought I saw a tear suspended on his long lashes. I took him to bed and he immediately fell asleep, his back to me. I spent the night worrying and only got to sleep in the early hours of the morning. I was losing him, but I was too proud to understand that his distance had nothing to do with me, that it was growing inside him and encompassed the whole world.

I woke with a start, his side of the bed empty. I found him in the living room, ready to leave. Nervous and pale, he told me that he had to go home. I was too exhausted to try to make him stay.

He stopped sending me updates and I didn’t message him, my pride wounded. All the same, I thought about him every day. I was more and more worried. I decided to reach out to him again, but my messages went unanswered, and so did my calls. So, I went to his place.

In the foyer, I notice that his letterbox is overflowing. I doubt that he’ll open the door, but at the first ring, after glancing through the peephole, he lets me in and locks the door behind him. I’m shocked: he’s pale, skin and bone, his eyes bulging and irritated. He’s wearing a mask and gloves, booties over his feet, and he’s feverish and agitated. A strong smell of chemical products hits me, to the point that I clamp my hands over my mouth. The room is so cluttered that you can hardly take a step, with rackets strewn on the floor, and two new insect traps sitting on the bed.

Mask lowered, he whispers,

“They’re everywhere, I can see them. But I’m going to win.”

There are no flies.

Panic seizes me and the fumes sting my throat. I take out my phone and dial an ambulance. Wild with rage, he snatches the phone from my hands and throws it across the room.

« Qu’est ce que tu fais ? Personne ne doit venir, JE vais les exterminer !»

“What are you doing? I don’t need any help! I’ll kill them myself!” His voice cracks with fury. For a moment, I’m afraid that he’s going to hit me, and I crouch down, my arms over my head. But it’s the plaster that takes the blow, blood mixing with the red paint of his walls. I catch sight of my phone; grab hold of it and rush into the little bathroom. Locking the door, I call an ambulance.

He screams, voice distorted, hits out again, shouts insults at me. I bite down on a towel until my jaw hurts; it doesn’t do much to protect me from the reek of detergent, even more intense in this cramped room. I clench my eyes shut, my whole body tense, curled up at the back of his shower with my knees against my chest, as far as possible from the door that he has started to hammer on.

Disturbed by the noise, his neighbours are at the door of his apartment. Hearing their knocks, and their voices, stops him short.

Silence. The beating of my heart seems to resound through the room.

I don’t know how long I remain frozen. When I decide to cautiously open the door, I find him sitting at his desk, very calm, looking exhausted. I approach him nervously. His fists are bloodied, there’s blood everywhere. He wipes his face, unknowingly painting a wide red streak that smears to his eyelashes, his chin. I crouch next to him. He leans his head down onto my shoulder and I wrap my arms around him. Everything is calm.

When the emergency services arrived, he opened the door, took his long black coat and followed them docilly into the ambulance; I don’t know if he was stunned or resigned.

I gave brief answers to their routine questions; I’ll follow them to the hospital but first I want to collect some of his things and find his phone to call his family. Alone in his apartment, I find some flies in the sink, dead. I remove the glass over the drain – a fly emerges, followed by a second, a third, a fourth. An uninterrupted stream of flies pours out of the drain and onto my face, catching in my hair, sticking in my eyes, crawling into my nose. I scream and they swarm into my mouth, I feel them at the back of my throat, cutting off my breath. My screams stop and I fall.